Even though I rarely have time to watch as much anime as I’d like, I’m usually pretty abreast of the noteworthy shows of each season, their names quietly chronicled in an ever expanding list of things I’ll watch “someday.” But somehow, Your Lie in April completely eluded me. It’s not that I hadn’t heard the title—it’s kind of catchy that way—but the particulars escaped me. It wasn’t until my sister brought it to my attention that I realized how much I needed to see this show. Pensive piano prodigy who has lost the ability to “hear” his music after the death of his demanding mother-slash-instructor is dragged from his bland grey world into a dazzling symphony of color by a vibrant, vivacious violinist? Sign me up! As Kousei (the aforementioned prodigy) grows closer to Kaori (the violinist), he learns to leave behind the perfect-yet-emotionless playing of his contest-winning childhood to embrace playing music for the love of music itself. As the opening credits say, “I met the girl under full-bloomed cherry blooms, and my fate has begun to change.”

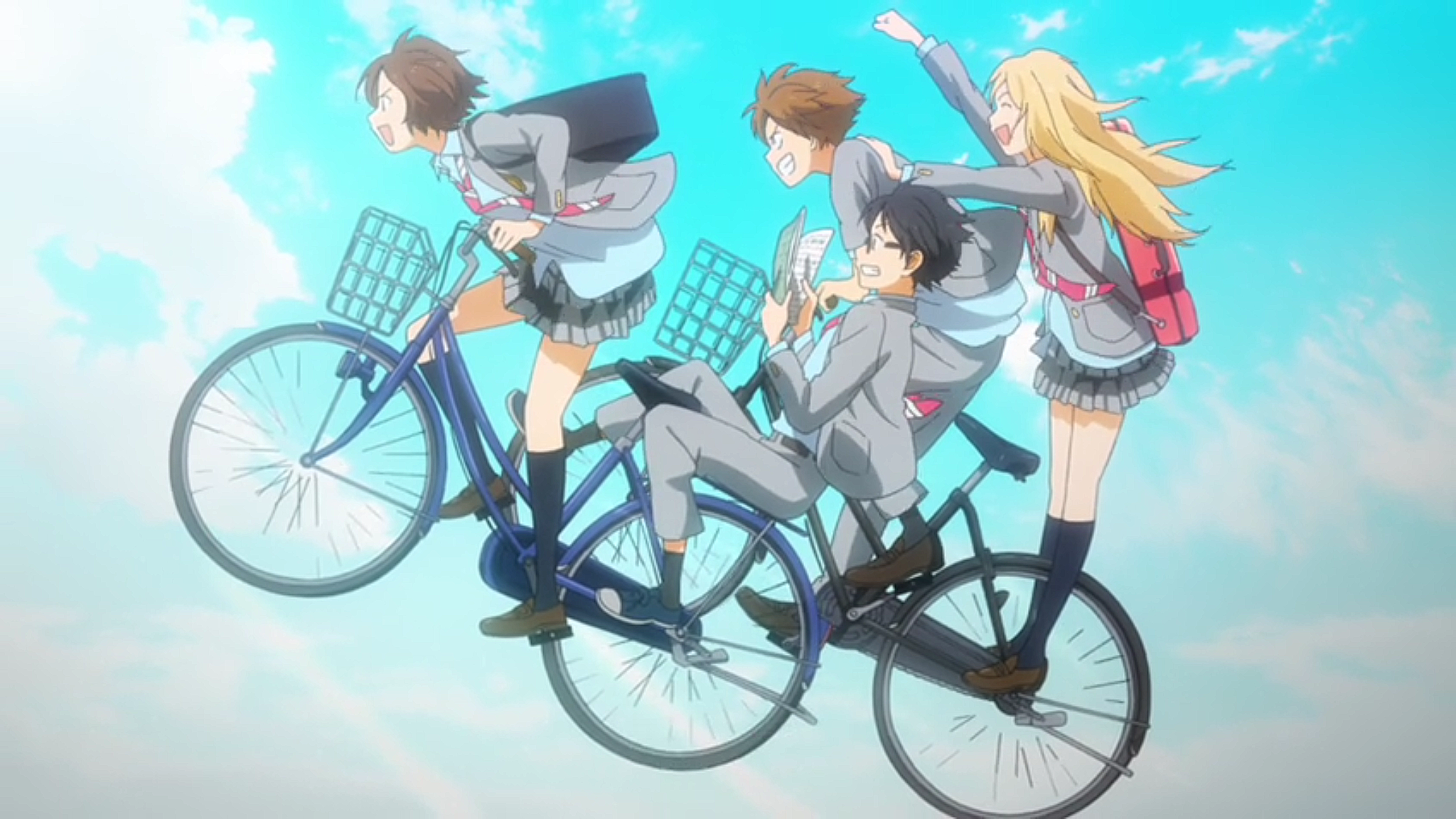

Fittingly, Your Lie in April is possibly the prettiest anime I’ve ever watched. Almost every frame is, well, frame-able, with enough cherry blossoms dancing by to fill one of the show’s many musical venues to capacity. It’s somewhat telling that the narrative skips through summer in quick tempo in order to portray similar feats of ambiance and beauty with the falling leaves of autumn. It would be easy to say that Your Lie is too pretty for its own good, shoveling in the sakura until nothing really stands out. But that’s where the show’s most surprising, and most brilliant, juxtaposition comes in. Despite weaving a tale traversing the depths of human feeling, the show breaks up the heaviness with full-on bouts of comedy. Characters super-deform, light on fire, human torpedo each other, and otherwise elicit the kind of silliness that, at first, seems out of place. But it’s this constant reminder of levity that keeps the show from becoming a mirthless slog.

Fittingly, Your Lie in April is possibly the prettiest anime I’ve ever watched. Almost every frame is, well, frame-able, with enough cherry blossoms dancing by to fill one of the show’s many musical venues to capacity. It’s somewhat telling that the narrative skips through summer in quick tempo in order to portray similar feats of ambiance and beauty with the falling leaves of autumn. It would be easy to say that Your Lie is too pretty for its own good, shoveling in the sakura until nothing really stands out. But that’s where the show’s most surprising, and most brilliant, juxtaposition comes in. Despite weaving a tale traversing the depths of human feeling, the show breaks up the heaviness with full-on bouts of comedy. Characters super-deform, light on fire, human torpedo each other, and otherwise elicit the kind of silliness that, at first, seems out of place. But it’s this constant reminder of levity that keeps the show from becoming a mirthless slog.

Calling Your Lie in April a realistic exploration of the human condition is a stretch. As they struggle with love and loss, most of its fourteen-year-old cast spout poetic treatises and wax nostalgia like middle-aged wordsmiths, but that’s okay. Lie is like the music it so throughly admires throughout the show. It is an idealized form of expression, carefully crafted to elicit the strongest emotional response. Whereas Erased celebrated the every day with its loving vignettes, Your Lie in April exalts it, creating a tapestry of the slice-of-life at its absolute most heart-wrenchingly beautiful.

Calling Your Lie in April a realistic exploration of the human condition is a stretch. As they struggle with love and loss, most of its fourteen-year-old cast spout poetic treatises and wax nostalgia like middle-aged wordsmiths, but that’s okay. Lie is like the music it so throughly admires throughout the show. It is an idealized form of expression, carefully crafted to elicit the strongest emotional response. Whereas Erased celebrated the every day with its loving vignettes, Your Lie in April exalts it, creating a tapestry of the slice-of-life at its absolute most heart-wrenchingly beautiful.

And the music! Your Lie is a tour-de-force of classical greats, and love and care is given to portraying and animating the instruments that produce it. There’s some 3D wizardry at work here, which normally rubs me the wrong way, but I think the complicated workings of playing such intricate piano pieces couldn’t be served any other way. Like everything else, every performance is rife with tension as the show’s characters struggle to command the music to their will. These are not mere pieces for a passive audience, but a powerful energy that can traverse time and space—to send a message that the performers desperately hope will reach and be understood. Even the audience listens with dramatic intensity, noting every sway of the performer’s will and even commenting with the musical equivalent of “His power level is over NINE-THOUUUSANND!”

And the music! Your Lie is a tour-de-force of classical greats, and love and care is given to portraying and animating the instruments that produce it. There’s some 3D wizardry at work here, which normally rubs me the wrong way, but I think the complicated workings of playing such intricate piano pieces couldn’t be served any other way. Like everything else, every performance is rife with tension as the show’s characters struggle to command the music to their will. These are not mere pieces for a passive audience, but a powerful energy that can traverse time and space—to send a message that the performers desperately hope will reach and be understood. Even the audience listens with dramatic intensity, noting every sway of the performer’s will and even commenting with the musical equivalent of “His power level is over NINE-THOUUUSANND!”

It’s utterly preposterous, of course, but somehow—like the rest of Your Lie in April—it is in its way the most honest. This melodramatic, over-the-top rendition of the humble musical performance conveys, just a small fragment, of the actual feelings that music can imbue. The show’s own score, while more limited in variety than the many classical composers it features, manages to stir up the heartstrings regardless of how many times you hear the main dramatic theme.

And despite the show’s many dips into melancholy, I appreciate that Your Lie is always up front and honest about it. The show’s main “twist”—if you can really call it that—is telegraphed so early and often that its reveal doesn’t feel like an ambush. The show’s drive for emotion never feels contrived or unfair. In fact, I think the real lie in Your Lie in April is the one you tell yourself. Until the show’s tear-jerking finale, I found myself hoping against hope that, perhaps, another resolution was possible.

And despite the show’s many dips into melancholy, I appreciate that Your Lie is always up front and honest about it. The show’s main “twist”—if you can really call it that—is telegraphed so early and often that its reveal doesn’t feel like an ambush. The show’s drive for emotion never feels contrived or unfair. In fact, I think the real lie in Your Lie in April is the one you tell yourself. Until the show’s tear-jerking finale, I found myself hoping against hope that, perhaps, another resolution was possible.

In the end, every piece of music has its end, its finale, its coda. And Your Lie in April finishes exactly where it had to all along.

Your Lie in April and OVA

Given how much vim and vigor is generously applied to Your Lie in April’s many performances, it’s actually really appropriate to represent the rise and fall of a given performer’s playing, confidence, and will with a few custom rules.

When a performer—whether that’s a pianist, a singer, or even a stand-up comedian—gets on the stage, they are immediate faced by their audience. Sometimes, the entire audience matters. Other times, it is only a choice few, be it trying to capture the heart of a loved one or impressing the hard-nosed judge. Whatever the case, the audience is given a DN based on how hard they are to impress. A fun night out at karaoke is prone to require a paltry 4 or 6, while world competitions may require 12—and beyond!

When a performer—whether that’s a pianist, a singer, or even a stand-up comedian—gets on the stage, they are immediate faced by their audience. Sometimes, the entire audience matters. Other times, it is only a choice few, be it trying to capture the heart of a loved one or impressing the hard-nosed judge. Whatever the case, the audience is given a DN based on how hard they are to impress. A fun night out at karaoke is prone to require a paltry 4 or 6, while world competitions may require 12—and beyond!

But performances are rarely the matter of a single roll. A good performance requires consistency and stamina. The Game Master will determine the number of successful rolls required to make a performance successful, and also the maximum number of rolls that can be made. The number of rolls is not necessarily the length of the performance itself, but a measure of the dramatic weight the performance carries. A night like many other nights in a concert tour may be handled by relatively few rolls, while one song in the ultimate final performance of a tournament may require many. Likewise, too many missteps, false starts, and errors will bring the performance to a crashing halt, even if there were great successes along the way. In between each roll, Players should take the time to role play their experience, whether they are the performer or the audience.

Digging Deep

A performer’s skill will take them a long way—but sometimes it is not enough. No amount of practice or aptitude can stave away the threat of one bad roll too many. By spending Endurance, Players can earn Drama Dice to improve their results. Sweat drips off their brow, the score bends to their will, and for that moment the very soul of their playing is channeled through their instrument and into the audience. In fact, performers can do this even if they succeeded already. After all, wouldn’t an Amazing Success be that much more…amazing?

But this emotion is not always appropriate. There are competitions where playing to the composer’s intent, by every note and measure, is required. In these cases, spending Drama Dice may disqualify the performer on technical merit alone. But audience choice—well, that’s another matter entirely, isn’t it?

Demons

Alas, performers don’t exist in a vacuum. As intently as they might focus on their performance, the outside world can threaten to break in and disrupt all they have struggled to achieve. Doubts, fears, past traumas and current stress all can meddle with the ability to perform. When such Demons rear their ugly heads, they make a roll. Minor worries might be represented as two dice, while persistent dreads can roll five dice or more. If the Demon roll ever beats the character’s own performance roll, it cancels it out, even if it would have been a success! Of course, characters may still dig deep to overcome them.

Speaking of music, readers, do you have a favorite anime with that subject as its focus? How about your favorite anime soundtrack? Tell me about it in the comments! Also, if you’d like to support this blog, consider purchasing Your Lie in April merchandise like comics, Blu-ray boxsets, and figures from this link!

Speaking of music, readers, do you have a favorite anime with that subject as its focus? How about your favorite anime soundtrack? Tell me about it in the comments! Also, if you’d like to support this blog, consider purchasing Your Lie in April merchandise like comics, Blu-ray boxsets, and figures from this link!

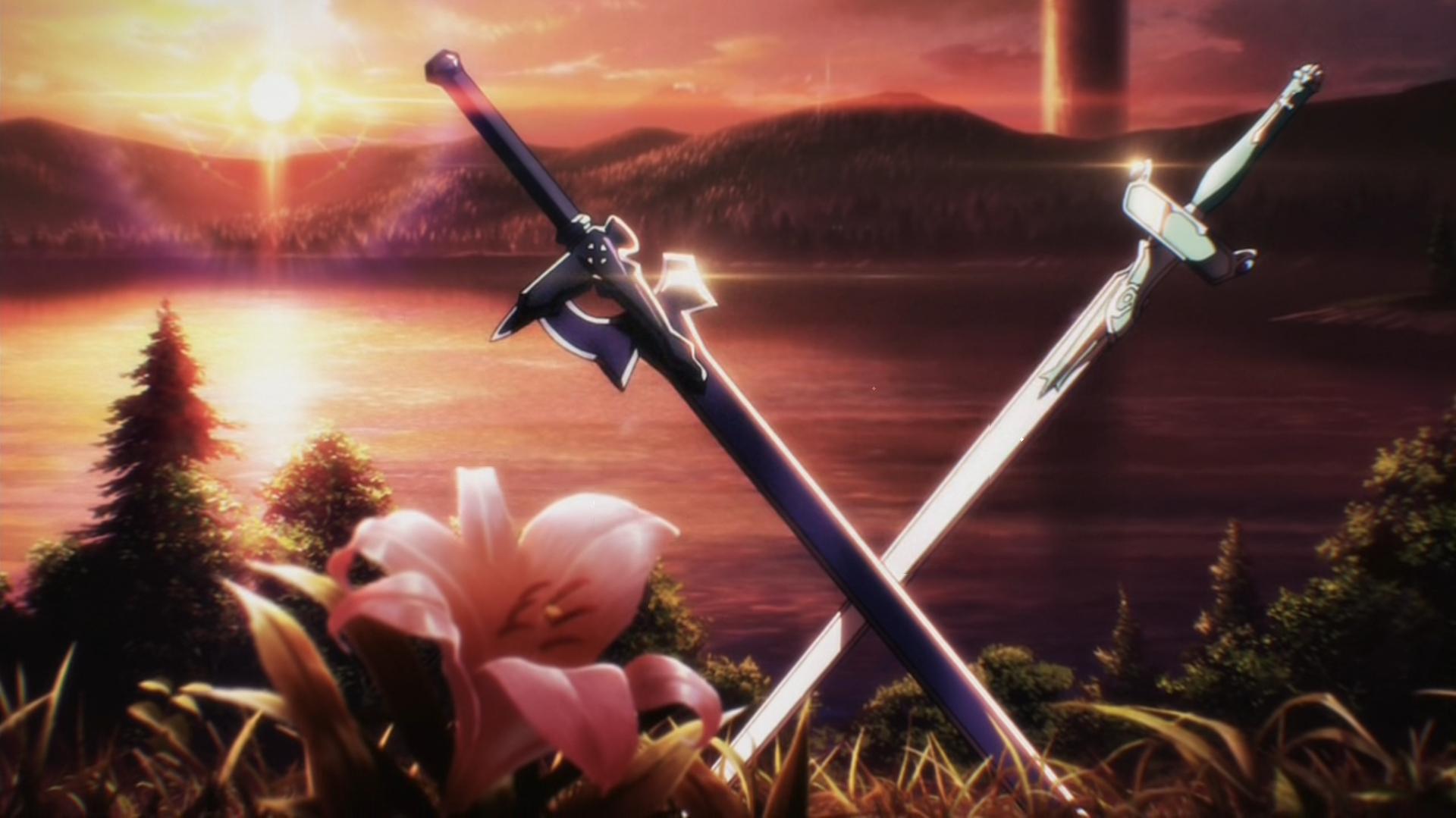

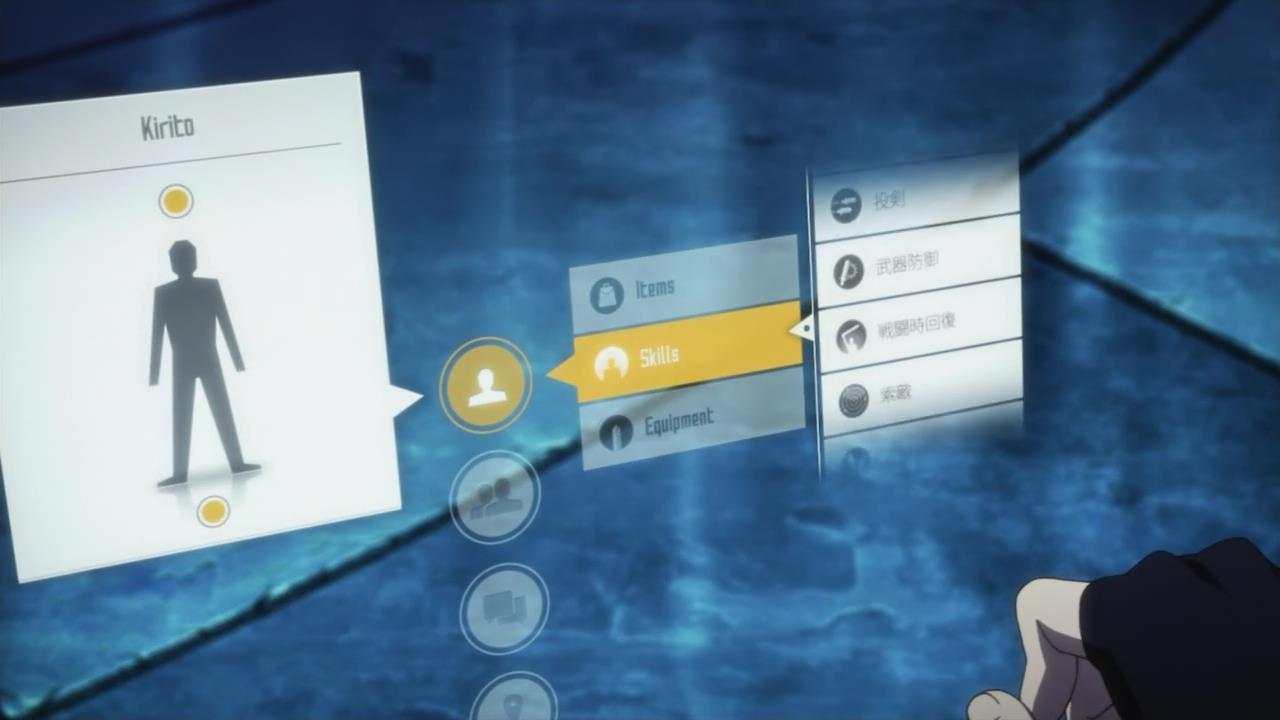

That’s because SAO is dedicated making the game world more than just window dressing. While its collection of rules and concepts are not always objectively sound if presented in a “real” MMORPG, Sword Art Online weaves its unique brand of video game logic through every layer of the narrative. Whether it’s the ebb and flow of its gorgeously animated, adrenaline-pumping battles and PvP duels, the fulfillment of quest lines and their requisite rare drops, or an entire episode devoted to a murder mystery wherein the culprit seemingly breaks the laws of SAO’s reality, the show never lets you forget that the world of Aincrad is part of a game. Even the protagonist, Kirito, has much of his golden-boy power and plot invulnerability explained by his previous experience as a beta tester. It’s great fun, and this exploration of the game itself is a piece of the puzzle .hack//SIGN glossed over in its version of the stuck in a video game tale.

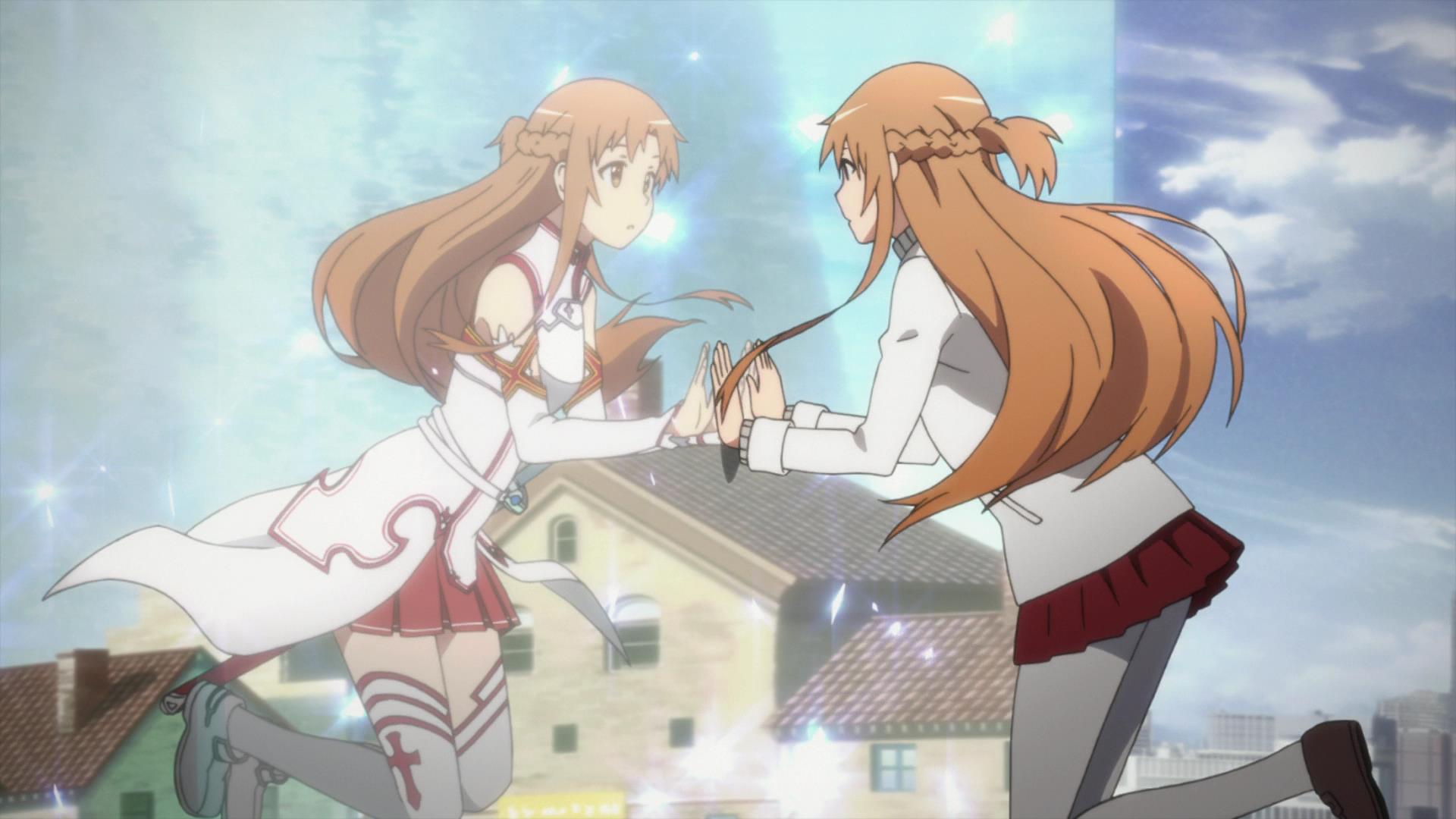

That’s because SAO is dedicated making the game world more than just window dressing. While its collection of rules and concepts are not always objectively sound if presented in a “real” MMORPG, Sword Art Online weaves its unique brand of video game logic through every layer of the narrative. Whether it’s the ebb and flow of its gorgeously animated, adrenaline-pumping battles and PvP duels, the fulfillment of quest lines and their requisite rare drops, or an entire episode devoted to a murder mystery wherein the culprit seemingly breaks the laws of SAO’s reality, the show never lets you forget that the world of Aincrad is part of a game. Even the protagonist, Kirito, has much of his golden-boy power and plot invulnerability explained by his previous experience as a beta tester. It’s great fun, and this exploration of the game itself is a piece of the puzzle .hack//SIGN glossed over in its version of the stuck in a video game tale. And Asuna, the show’s requisite waifu for Kirito, far exceeds such a label. That’s because Asuna is more than a damsel backdrop for Kirito to show off his mettle. If anything, Asuna carries the show. While Kirito has his beta test experience and a few convenient plot abilities to fall back on, Asuna’s aptitude at the game was tempered in the game itself. She is on the front-lines despite not knowing the road ahead, and it is through her own conviction and power that the day is saved at critical moments throughout the show’s first story arc.

And Asuna, the show’s requisite waifu for Kirito, far exceeds such a label. That’s because Asuna is more than a damsel backdrop for Kirito to show off his mettle. If anything, Asuna carries the show. While Kirito has his beta test experience and a few convenient plot abilities to fall back on, Asuna’s aptitude at the game was tempered in the game itself. She is on the front-lines despite not knowing the road ahead, and it is through her own conviction and power that the day is saved at critical moments throughout the show’s first story arc. That’s not to say the second arc is bad. It’s perfectly watchable, and despite fan outrage that I largely chalk up to “She’s not Asuna,” Sugaha/Leafa is cute and likeable. It just doesn’t deliver on the promise exhibited in the earlier episodes, instead falling hook, line, and sinker into the mire of expectations it so expertly cast off before.

That’s not to say the second arc is bad. It’s perfectly watchable, and despite fan outrage that I largely chalk up to “She’s not Asuna,” Sugaha/Leafa is cute and likeable. It just doesn’t deliver on the promise exhibited in the earlier episodes, instead falling hook, line, and sinker into the mire of expectations it so expertly cast off before.

This Flinch complication is inflicted in one of two ways: One is by dealing any other combat complication, which will also inflict the Flinched status. The other is reserved for enemies with large, heavy-hitting weapons or attacks. If they should ever attack a character but deal no damage, they are immediately put into the Flinched state.

This Flinch complication is inflicted in one of two ways: One is by dealing any other combat complication, which will also inflict the Flinched status. The other is reserved for enemies with large, heavy-hitting weapons or attacks. If they should ever attack a character but deal no damage, they are immediately put into the Flinched state.

While I am loath to do any major spoiling in my overview here, I think it is a testament to the show that for all its turnarounds and revelations, it holds up to repeat viewings and—dare I say—is possibly better for it. Motivations that seemed arcane before are clear, and countless details unnoticeable the first time around are scattered throughout the narrative. And for all its slow pacing for the early part of the show, Madoka sets up what will be its biggest strength: The show really isn’t about Madoka at all. When you discover the heart of the matter, every frame becomes a cherished part of the whole.

While I am loath to do any major spoiling in my overview here, I think it is a testament to the show that for all its turnarounds and revelations, it holds up to repeat viewings and—dare I say—is possibly better for it. Motivations that seemed arcane before are clear, and countless details unnoticeable the first time around are scattered throughout the narrative. And for all its slow pacing for the early part of the show, Madoka sets up what will be its biggest strength: The show really isn’t about Madoka at all. When you discover the heart of the matter, every frame becomes a cherished part of the whole.

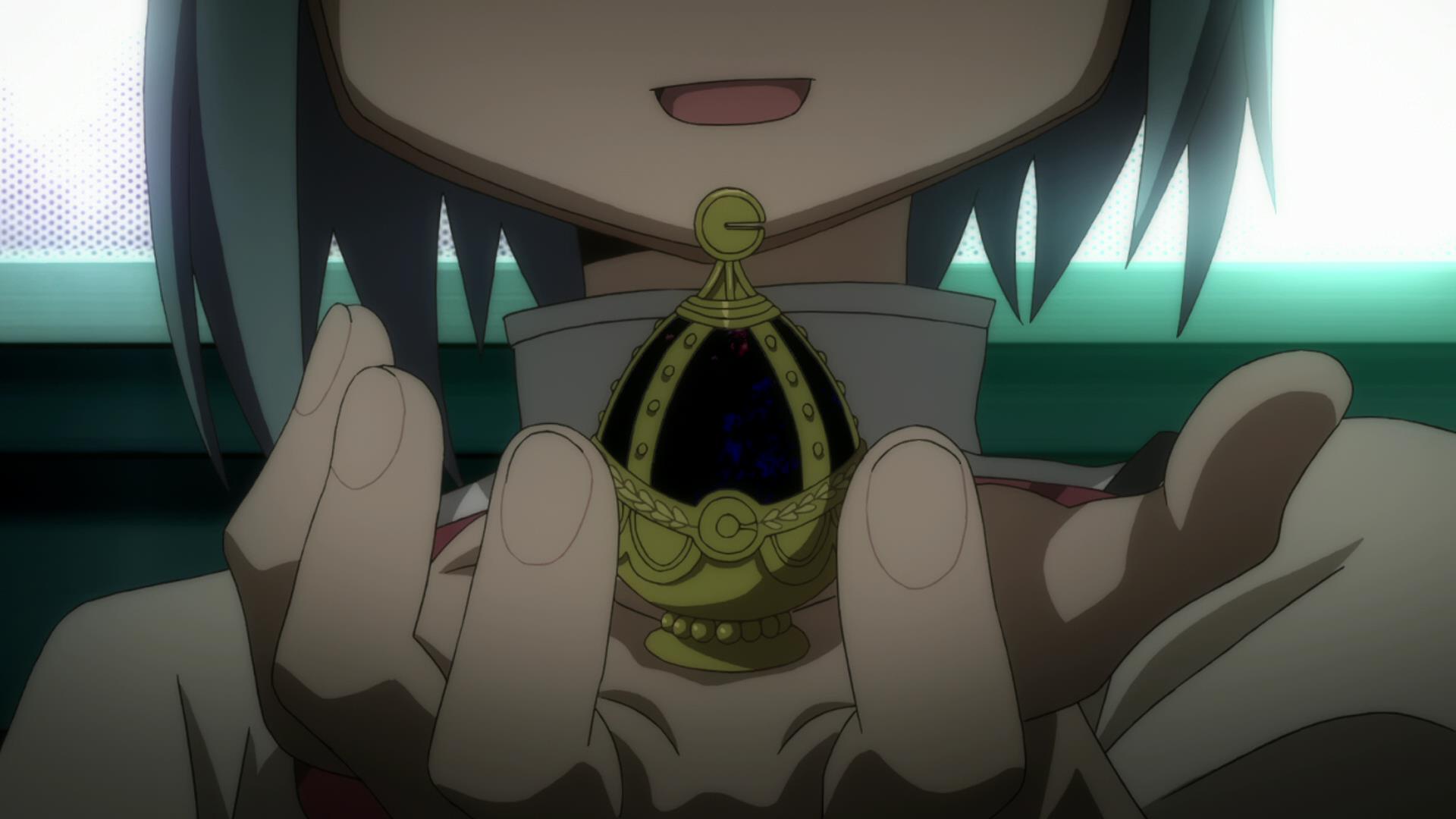

Because a magical girl’s soul lies within her gem, and the human body has become merely a shell for action, should the distance between the body and the gem grow too far, the ability to control the body is lost and it becomes effectively dead. As long as they are reunited, the magical girl can continue on as before, but if they are not…

Because a magical girl’s soul lies within her gem, and the human body has become merely a shell for action, should the distance between the body and the gem grow too far, the ability to control the body is lost and it becomes effectively dead. As long as they are reunited, the magical girl can continue on as before, but if they are not…

It’s an intriguing premise on its own, but when the death of someone close to Satoru results in him being framed for the crime, Revival kicks into overdrive and send him all the way back to 1988—to his childhood days where he and his classmates experience the abduction and death of fellow students. As an adult-minded Satoru relives his youth, he realizes that these murders may be the source of his misfortune in the present, perhaps the origin of everything, and he sets out to change the future.

It’s an intriguing premise on its own, but when the death of someone close to Satoru results in him being framed for the crime, Revival kicks into overdrive and send him all the way back to 1988—to his childhood days where he and his classmates experience the abduction and death of fellow students. As an adult-minded Satoru relives his youth, he realizes that these murders may be the source of his misfortune in the present, perhaps the origin of everything, and he sets out to change the future. This especially true since Satoru’s success in changing the future has as much to do with changing his relationships in the past as it does his detective work. His efforts to keep Kayo, the serial killer’s first victim, from being vulnerable and alone develop into much more, as they each discover the truth in each other and the insecurities he didn’t fully understand as a child. It’s not just Kayo, either, as Satoru reaches out and makes deeper, more profound connections with his core circle of friends, eventually enlisting them on his quest to thwart the dismal future.

This especially true since Satoru’s success in changing the future has as much to do with changing his relationships in the past as it does his detective work. His efforts to keep Kayo, the serial killer’s first victim, from being vulnerable and alone develop into much more, as they each discover the truth in each other and the insecurities he didn’t fully understand as a child. It’s not just Kayo, either, as Satoru reaches out and makes deeper, more profound connections with his core circle of friends, eventually enlisting them on his quest to thwart the dismal future. The show deftly juggles the murder mystery and everyday life, Satoru’s past and present, and spans of calm and drama in a way that neither ever outlives its welcome. It’s a mixture that thrives on each other, and the show’s pacing perfectly sets up the conclusion in a way that imminently satisfying. That’s not to say the show is without faults. One of the main antagonist’s characterization is embarrassingly thin; even the serial killer that serves as the catalyst for the entire story isn’t much better. But that’s okay, because the story isn’t really about them. It isn’t really even about the murder mystery. It’s about people treating each other with kindness, learning to see past the failings of ourselves and others, past the barriers we erect around us. And connect.

The show deftly juggles the murder mystery and everyday life, Satoru’s past and present, and spans of calm and drama in a way that neither ever outlives its welcome. It’s a mixture that thrives on each other, and the show’s pacing perfectly sets up the conclusion in a way that imminently satisfying. That’s not to say the show is without faults. One of the main antagonist’s characterization is embarrassingly thin; even the serial killer that serves as the catalyst for the entire story isn’t much better. But that’s okay, because the story isn’t really about them. It isn’t really even about the murder mystery. It’s about people treating each other with kindness, learning to see past the failings of ourselves and others, past the barriers we erect around us. And connect.

Revival—Time does not flow smoothly for you. When great misfortune, harm, or other danger happens around you, your life’s clock rewinds a few precious seconds, giving you a second chance to notice what has gone wrong. This awareness is not automatic, as you only know that you have jumped back into the past, not the exact reason for it. The greater your level in Revival, the more time your character rewinds backward, giving you longer to assess the situation and act upon it. Add your Revival Dice to any actions you manage to take during the span of time that you repeat. If you can’t discover the reason for the Revival (with Abilities like Perceptive or Sixth Sense) or act on them in time, the Revival and its Bonus dice end.

Revival—Time does not flow smoothly for you. When great misfortune, harm, or other danger happens around you, your life’s clock rewinds a few precious seconds, giving you a second chance to notice what has gone wrong. This awareness is not automatic, as you only know that you have jumped back into the past, not the exact reason for it. The greater your level in Revival, the more time your character rewinds backward, giving you longer to assess the situation and act upon it. Add your Revival Dice to any actions you manage to take during the span of time that you repeat. If you can’t discover the reason for the Revival (with Abilities like Perceptive or Sixth Sense) or act on them in time, the Revival and its Bonus dice end.

But Spike isn’t just sort of good at both, he’s great. And if you couldn’t create Spike with ease in OVA, then that’s as much of a litmus test as anything. With that in mind, I condensed every combat skill into an Ability called, well, Combat Skill. With one attribute, your character was adept at attacking, whatever form that takes. Sure, it flies in the face of most RPG design that routinely compartmentalize such things, but it just made things so much easier. You could still just do one thing, of course, but if you ever wanted to branch out, you weren’t punished for it.

But Spike isn’t just sort of good at both, he’s great. And if you couldn’t create Spike with ease in OVA, then that’s as much of a litmus test as anything. With that in mind, I condensed every combat skill into an Ability called, well, Combat Skill. With one attribute, your character was adept at attacking, whatever form that takes. Sure, it flies in the face of most RPG design that routinely compartmentalize such things, but it just made things so much easier. You could still just do one thing, of course, but if you ever wanted to branch out, you weren’t punished for it. While this was easily the most gratifying change to OVA, there’s a vast variety of additions and improvements that I’m also fond of. The original game’s “knockback” was split into three separate combat complications, giving more tactical options to the otherwise streamlined rules. Looking at these, I realized that I could take the same concept and apply them outside of combat, and Succeeding with Complications was born. While I won’t be foolhardy enough to claim this is an entirely new idea (Fate, if nothing else, pushes the “fail forward” concept hard), I’m really please with how neatly it fits into OVA and brings combat and out-of-combat closer together thematically.

While this was easily the most gratifying change to OVA, there’s a vast variety of additions and improvements that I’m also fond of. The original game’s “knockback” was split into three separate combat complications, giving more tactical options to the otherwise streamlined rules. Looking at these, I realized that I could take the same concept and apply them outside of combat, and Succeeding with Complications was born. While I won’t be foolhardy enough to claim this is an entirely new idea (Fate, if nothing else, pushes the “fail forward” concept hard), I’m really please with how neatly it fits into OVA and brings combat and out-of-combat closer together thematically.

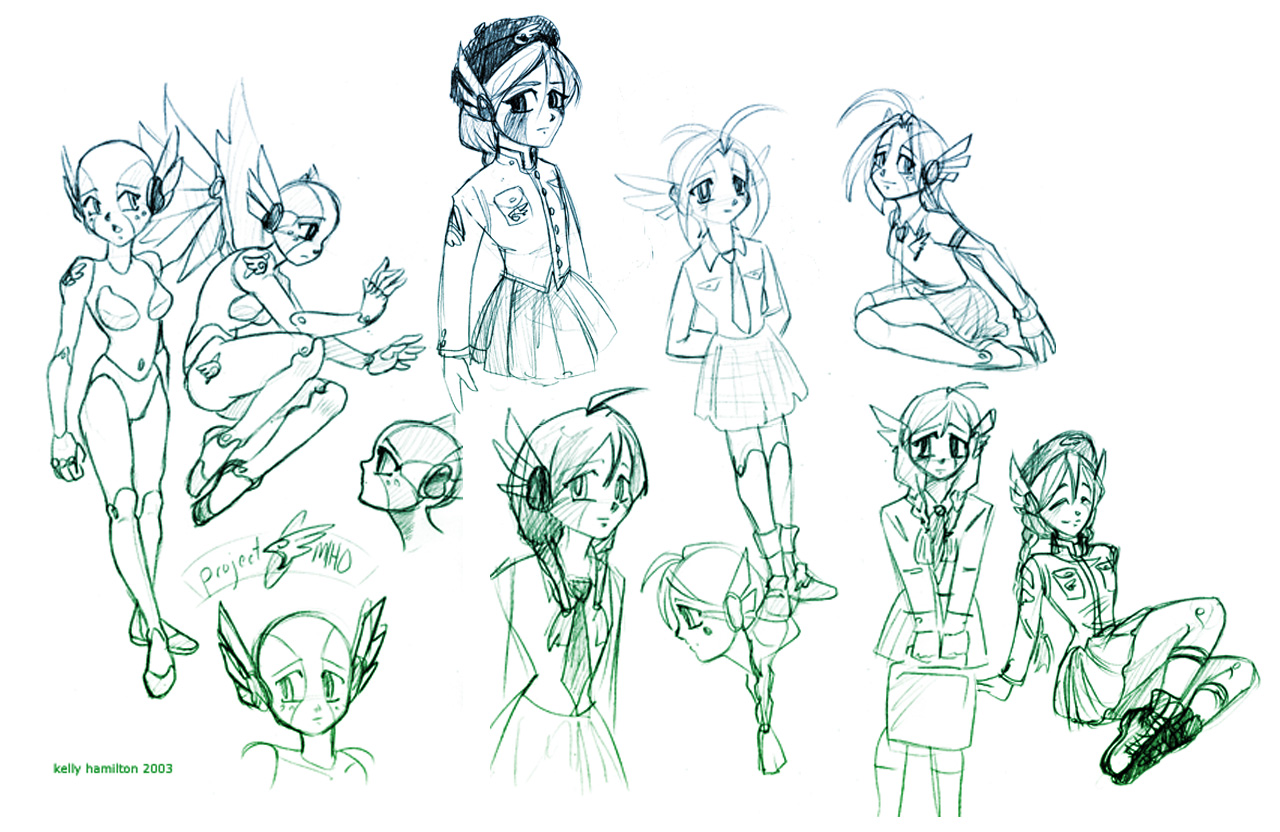

The military-inspired uniform makes its first appearance here and was used for her final design. This iconic ensemble would go on to be featured (more or less) in the revised game, despite the fact that most other character designs changed completely.

The military-inspired uniform makes its first appearance here and was used for her final design. This iconic ensemble would go on to be featured (more or less) in the revised game, despite the fact that most other character designs changed completely. Oh, and if you’re wondering about my illustrations mentioned earlier, here’s a final comparison featuring everyone’s favorite copper, Jiro.

Oh, and if you’re wondering about my illustrations mentioned earlier, here’s a final comparison featuring everyone’s favorite copper, Jiro. Slight improvement, right?

Slight improvement, right?

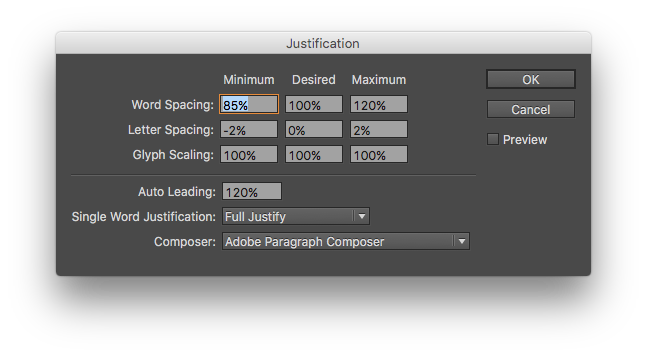

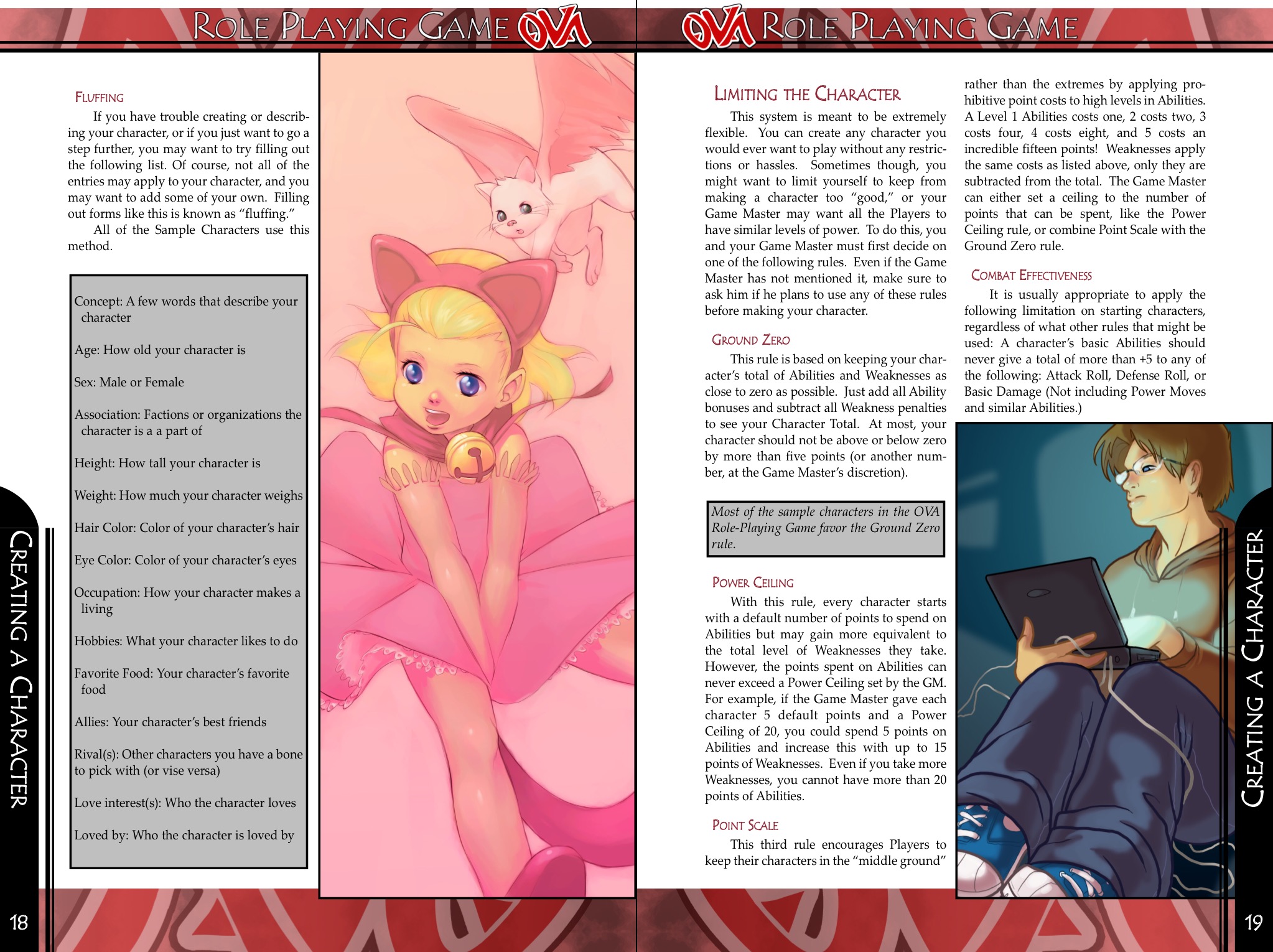

I chose this set of pages because it’s one of the few spreads that remained effectively identical between the versions with text and art placement. I think it demonstrates the difference a bit of experience makes pretty well! There are a lot of things I could point out, but here are some of the biggest points of advice I can share.

I chose this set of pages because it’s one of the few spreads that remained effectively identical between the versions with text and art placement. I think it demonstrates the difference a bit of experience makes pretty well! There are a lot of things I could point out, but here are some of the biggest points of advice I can share.