Violet, despite being a young girl, is a veteran of war whose proficiency in combat is the stuff of legends. Her personal sacrifice is quickly made clear as she is revealed to possess a pair of mechanical arms. Having only known war, adjusting to these prosthetics only further complicates her transition to a normal life. As she struggles to do so, and find the meaning of her beloved Major’s last words to her, Violet sees a path to understanding via the vocation of Auto Memory Doll—a job where one strives to put down their clients’ feelings in carefully crafted letters. Even her clumsy, mechanical hands can use a typewriter, though understanding the nature of the human heart is a battle all its own.

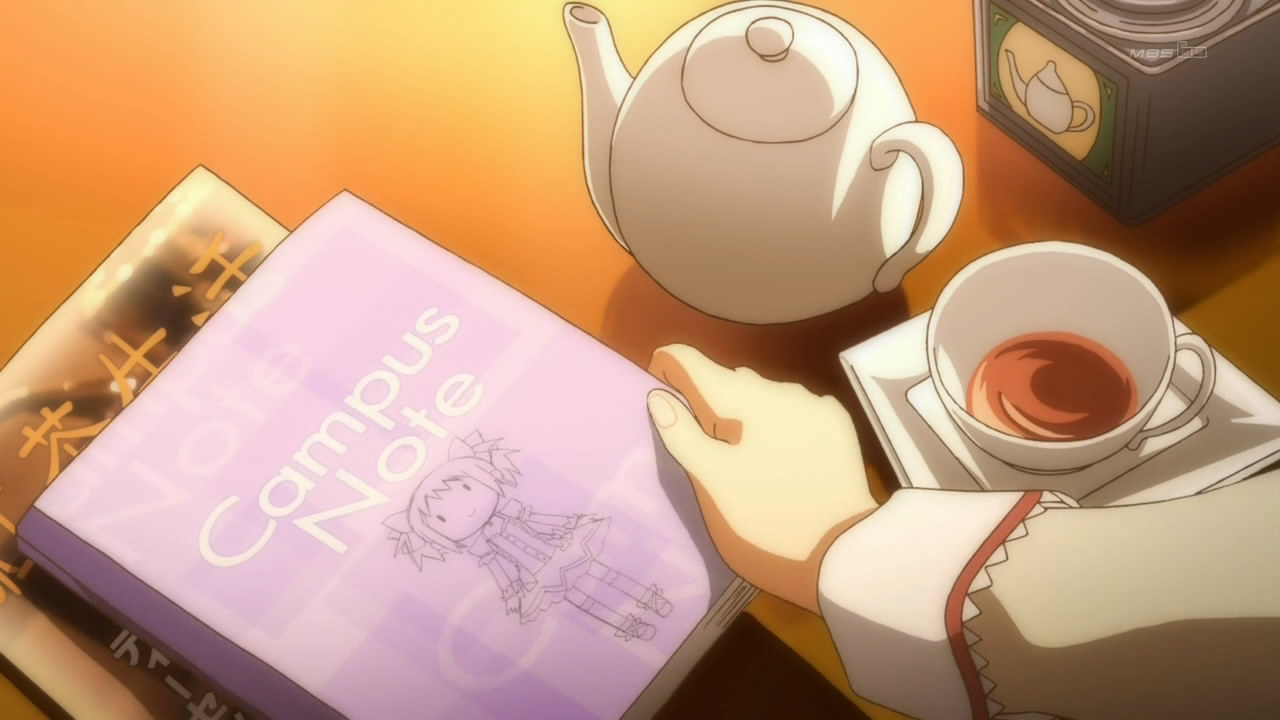

Violet Evergarden is a love letter to a mid-twentieth-century Europe that never was, with sumptuously rendered backdrops of bustling streets and pastoral countryside, and animation that pours love for frilly dresses that bob with every curtsy, intricately braided hair occasionally frazzled from emotional outpourings, and even flowers delicately swaying in the breeze that serve as namesakes for many of the show’s characters. But more than that, Evergarden is a love letter to the love letter. The show exalts the power of the written word and its ability to convey what often cannot be said, to conjure the concrete from the ephemeral and deliver it to the person to which those words will hopefully belong.

Through its earnest striving to paint a picture of these emotions, though, the show often tries to tell us what to feel instead of making us feel it ourselves. Characters are a constant source of waterworks, but often their trials and tribulations are given too little time to mature, their triumphs and tragedies relegated to less than careful exposition, making the tears themselves bear the weight of the story’s emotional gravitas.

Through its earnest striving to paint a picture of these emotions, though, the show often tries to tell us what to feel instead of making us feel it ourselves. Characters are a constant source of waterworks, but often their trials and tribulations are given too little time to mature, their triumphs and tragedies relegated to less than careful exposition, making the tears themselves bear the weight of the story’s emotional gravitas.

But it is an understandable caveat of the show’s episodic nature. As Violet travels from town to town, it may be a little much to expect an entire arc of emotional storytelling, from character introduction to climax to denouement, in a completely nuanced way. Nonetheless, each episode is like a mystery where Violet brings her intuition to bear, to discover the true heart of those that commission her services. And this journey, truncated as it may be, is satisfying to follow along.

The show may be at its best, though, when we can peer more into Violet herself. While much of the time she exhibits a personality as flat as the dolls that her occupation’s name alludes to, the stark contrast amplifies her struggle to understand what it means to live a normal life. Her mechanical arms serve as a flashy, overt metaphor for her own emotional development—as she adjusts to their clumsy, unsubtle nature, so too does she shed the shell of her guarded personality…at least a little.

The show may be at its best, though, when we can peer more into Violet herself. While much of the time she exhibits a personality as flat as the dolls that her occupation’s name alludes to, the stark contrast amplifies her struggle to understand what it means to live a normal life. Her mechanical arms serve as a flashy, overt metaphor for her own emotional development—as she adjusts to their clumsy, unsubtle nature, so too does she shed the shell of her guarded personality…at least a little.

Yet, we never learn how Violet’s mechanical arms work in a world otherwise devoid of such technological marvels, any more than we learn about Violet’s own origins or the source of her amazing combat ability. But these details are incidental to her journey. Sometimes all you need is a typewriter and the right words—all these exactingly fashioned, carefully wrought, painstakingly perfected words to understand what it means when we say,

Yet, we never learn how Violet’s mechanical arms work in a world otherwise devoid of such technological marvels, any more than we learn about Violet’s own origins or the source of her amazing combat ability. But these details are incidental to her journey. Sometimes all you need is a typewriter and the right words—all these exactingly fashioned, carefully wrought, painstakingly perfected words to understand what it means when we say,

“I love you.”

Violet Evergarden and OVA

While it mostly serves as a vehicle for Violet’s own emotional development, the vocation of Auto Memory Doll is nonetheless central to the world of Violet Evergarden. It is a job that contains within it many facets and surpasses that of a simple transcriptionist. At their best, Auto Memory Dolls are part detective, part therapist, striving to complete their clients hopes and aspirations through their letters.

Discovering One’s True Heart

The actual process of typing the letter is not a lengthy endeavor. An accomplished Auto Memory Doll can get the job done in a single visit with the client. In OVA, you could easily represent this with a single roll of the dice (perhaps using a new Unique Ability, Auto Memory Doll, to represent the character’s skill), if you even roll dice at all.

But other times, getting to the bottom of what the client wants to say requires more effort. The Auto Memory Doll must study the client and pick up on the subtle clues to their true feelings, feelings the client themselves may not be fully aware of. Some of these clues can be gathered through a Perceptive roll, others may require Charismatic, and still others require Intuitive and actual investigation.

Each time the Auto Memory Doll discovers a clue to the client’s true heart, they collect a special Auto Memory Doll die. When they determine they have learned enough, or simply time has run out, these can be added to the Letter Writing roll.

Writing the Letter

When it comes time to write the letter, the Auto Memory Doll rolls all dice that apply. At its simplest, this can be covered by Unique Ability: Auto Memory Doll, but it can also be split up into different sub-facets, like Grammar, Empathy, and Poetry. On the other hand, you can simply use the Abilities already in OVA that apply.

When it comes time to write the letter, the Auto Memory Doll rolls all dice that apply. At its simplest, this can be covered by Unique Ability: Auto Memory Doll, but it can also be split up into different sub-facets, like Grammar, Empathy, and Poetry. On the other hand, you can simply use the Abilities already in OVA that apply.

In addition, include all Auto Memory Doll dice earned during the course of the game session. The result represents the quality and accuracy of the letter, and it is compared to a Client Difficulty based on numerous factors. Lower DNs represent open-hearted clients with easy-to-please recipients, while high DNs represent clients whose feelings are especially arcane or concealed or recipients that are especially unreceptive.

Her FranXX is nimble and bestial as we watch her fight. The klaxosaur is alien and frightening, immediately casting an ominous shadow as we stare death in the face. But Zero Two cannot defeat it alone. Despite his past failures, despite Zero Two’s fearsome reputation, Hiro volunteers to pilot with her. Sealing this pact with a kiss, Zero Two pilots with her “darling,” and we see the true form of the FranXX as it transforms…into a shapely, saucer-eyed battle bot.

Her FranXX is nimble and bestial as we watch her fight. The klaxosaur is alien and frightening, immediately casting an ominous shadow as we stare death in the face. But Zero Two cannot defeat it alone. Despite his past failures, despite Zero Two’s fearsome reputation, Hiro volunteers to pilot with her. Sealing this pact with a kiss, Zero Two pilots with her “darling,” and we see the true form of the FranXX as it transforms…into a shapely, saucer-eyed battle bot. Okay, okay, so far we’ve pretty much set up the exact plot line I expected, but as Darling continues on, it passes through phases of high school comedy, monster-of-the-week spectacular, fanservice vehicle, post-apocalyptic drama, sci-fi conspiracy epic, and well beyond. Just like the visual clash of the monstrous leonine FranXX and its girlish true form, the show is surprising and mercurial. At times, it’s as if Darling in the FranXX is never quite sure what show it wants to be. But yet, as we follow along with the adventures of Squad 13, all of these permutations, nigh haphazard as they are, fit perfectly with the show’s central theme. Darling is an exploration of what it means to grow up and all of the baggage of uncertainty that entails. Faced with a world that has largely left emotion and individuality behind, the kids are put at an even further disadvantage as they explore not just what it means to become an adult, but what it means to be human. (Even the rather…provocative…poses the pilots take in their FranXX is more than just cheap fanservice, but an overt metaphor for the relationships humanity has left behind.)

Okay, okay, so far we’ve pretty much set up the exact plot line I expected, but as Darling continues on, it passes through phases of high school comedy, monster-of-the-week spectacular, fanservice vehicle, post-apocalyptic drama, sci-fi conspiracy epic, and well beyond. Just like the visual clash of the monstrous leonine FranXX and its girlish true form, the show is surprising and mercurial. At times, it’s as if Darling in the FranXX is never quite sure what show it wants to be. But yet, as we follow along with the adventures of Squad 13, all of these permutations, nigh haphazard as they are, fit perfectly with the show’s central theme. Darling is an exploration of what it means to grow up and all of the baggage of uncertainty that entails. Faced with a world that has largely left emotion and individuality behind, the kids are put at an even further disadvantage as they explore not just what it means to become an adult, but what it means to be human. (Even the rather…provocative…poses the pilots take in their FranXX is more than just cheap fanservice, but an overt metaphor for the relationships humanity has left behind.) “What it means to be human” is a topic I put forth as a central tenet of anime in the “Telling Anime Stories” section of OVA, so it’s not exactly surprising to see it here. Yet Darling goes further than that. What does it mean to be an adult, when you’ve been told nothing about your future? What does it mean to love, when you don’t even know what a kiss is? What does it mean to be alive, when all you’ve been told how to do is fight…and die? Our heroes grapple with this and more as they strive to make a place for themselves in, and even save, this world. They have to define what they mean to each other, and what it means to mean something to each other, as they wrestle with love and unrequited love and what future they can hope for themselves beyond the culling of Klaxosaurs.

“What it means to be human” is a topic I put forth as a central tenet of anime in the “Telling Anime Stories” section of OVA, so it’s not exactly surprising to see it here. Yet Darling goes further than that. What does it mean to be an adult, when you’ve been told nothing about your future? What does it mean to love, when you don’t even know what a kiss is? What does it mean to be alive, when all you’ve been told how to do is fight…and die? Our heroes grapple with this and more as they strive to make a place for themselves in, and even save, this world. They have to define what they mean to each other, and what it means to mean something to each other, as they wrestle with love and unrequited love and what future they can hope for themselves beyond the culling of Klaxosaurs. These questions are difficult enough for the show’s young protagonists, but take on new nuances when applied to Zero Two. Being born from Klaxosaur blood, she is immediately “othered” despite her unparalleled ability to fight the Klaxosaurs themselves. Like Squad 13, she is valued for this prowess alone, but carries the extra burden of being a quote-unquote monster. As she strives along a course that she believes will bring her closer to being human, the real question becomes less “What does it mean to be human?” and more “what makes it so easy to define a thing we don’t understand as monstrous?”

These questions are difficult enough for the show’s young protagonists, but take on new nuances when applied to Zero Two. Being born from Klaxosaur blood, she is immediately “othered” despite her unparalleled ability to fight the Klaxosaurs themselves. Like Squad 13, she is valued for this prowess alone, but carries the extra burden of being a quote-unquote monster. As she strives along a course that she believes will bring her closer to being human, the real question becomes less “What does it mean to be human?” and more “what makes it so easy to define a thing we don’t understand as monstrous?” And as the characters become more confident, discover not the “right” answer to these questions but the answer they have discovered for themselves, Darling in the FranXX too matures into a show quite unlike its beginnings. This rapid evolution in the last third or so of the series was understandably divisive among fans, and you’ll see a great many discourses on how the show plummets once it reaches its endgame. But in the end, FranXX becoming something you didn’t expect—finding for itself its own definition of what it should be—is as good a metaphor for adulthood as anything. And even as the show rushes forth to this conclusion, abandoning the shackles of its youth with such speed that it stumbles over countless hurdles of exposition and casts aside almost entirely the world-building it has spent so much time developing on its way to the stars…

And as the characters become more confident, discover not the “right” answer to these questions but the answer they have discovered for themselves, Darling in the FranXX too matures into a show quite unlike its beginnings. This rapid evolution in the last third or so of the series was understandably divisive among fans, and you’ll see a great many discourses on how the show plummets once it reaches its endgame. But in the end, FranXX becoming something you didn’t expect—finding for itself its own definition of what it should be—is as good a metaphor for adulthood as anything. And even as the show rushes forth to this conclusion, abandoning the shackles of its youth with such speed that it stumbles over countless hurdles of exposition and casts aside almost entirely the world-building it has spent so much time developing on its way to the stars…

While ostensibly it is the stamen that pilots the FranXX, true effectiveness in battle requires open communication and compatibility between both FranXX pilots. Much like determining the Paracapacity score, both Players roll their Pilot dice when taking actions with the FranXX and determine their results as a combination of their dice. Either Player can choose the FranXX’s action for the turn, but in the case of disagreement, the stamen’s preference always takes precedence.

While ostensibly it is the stamen that pilots the FranXX, true effectiveness in battle requires open communication and compatibility between both FranXX pilots. Much like determining the Paracapacity score, both Players roll their Pilot dice when taking actions with the FranXX and determine their results as a combination of their dice. Either Player can choose the FranXX’s action for the turn, but in the case of disagreement, the stamen’s preference always takes precedence. Zero Two, and perhaps any pilot with Klaxosaur blood, can pilot in Stampede Mode indefinitely without this Endurance drain. However, without the stamen’s Pilot dice, the FranXX is still demonstratively less effective.

Zero Two, and perhaps any pilot with Klaxosaur blood, can pilot in Stampede Mode indefinitely without this Endurance drain. However, without the stamen’s Pilot dice, the FranXX is still demonstratively less effective.

Fittingly, Your Lie in April is possibly the prettiest anime I’ve ever watched. Almost every frame is, well, frame-able, with enough cherry blossoms dancing by to fill one of the show’s many musical venues to capacity. It’s somewhat telling that the narrative skips through summer in quick tempo in order to portray similar feats of ambiance and beauty with the falling leaves of autumn. It would be easy to say that Your Lie is too pretty for its own good, shoveling in the sakura until nothing really stands out. But that’s where the show’s most surprising, and most brilliant, juxtaposition comes in. Despite weaving a tale traversing the depths of human feeling, the show breaks up the heaviness with full-on bouts of comedy. Characters super-deform, light on fire, human torpedo each other, and otherwise elicit the kind of silliness that, at first, seems out of place. But it’s this constant reminder of levity that keeps the show from becoming a mirthless slog.

Fittingly, Your Lie in April is possibly the prettiest anime I’ve ever watched. Almost every frame is, well, frame-able, with enough cherry blossoms dancing by to fill one of the show’s many musical venues to capacity. It’s somewhat telling that the narrative skips through summer in quick tempo in order to portray similar feats of ambiance and beauty with the falling leaves of autumn. It would be easy to say that Your Lie is too pretty for its own good, shoveling in the sakura until nothing really stands out. But that’s where the show’s most surprising, and most brilliant, juxtaposition comes in. Despite weaving a tale traversing the depths of human feeling, the show breaks up the heaviness with full-on bouts of comedy. Characters super-deform, light on fire, human torpedo each other, and otherwise elicit the kind of silliness that, at first, seems out of place. But it’s this constant reminder of levity that keeps the show from becoming a mirthless slog. Calling Your Lie in April a realistic exploration of the human condition is a stretch. As they struggle with love and loss, most of its fourteen-year-old cast spout poetic treatises and wax nostalgia like middle-aged wordsmiths, but that’s okay. Lie is like the music it so throughly admires throughout the show. It is an idealized form of expression, carefully crafted to elicit the strongest emotional response. Whereas Erased celebrated the every day with its loving vignettes, Your Lie in April exalts it, creating a tapestry of the slice-of-life at its absolute most heart-wrenchingly beautiful.

Calling Your Lie in April a realistic exploration of the human condition is a stretch. As they struggle with love and loss, most of its fourteen-year-old cast spout poetic treatises and wax nostalgia like middle-aged wordsmiths, but that’s okay. Lie is like the music it so throughly admires throughout the show. It is an idealized form of expression, carefully crafted to elicit the strongest emotional response. Whereas Erased celebrated the every day with its loving vignettes, Your Lie in April exalts it, creating a tapestry of the slice-of-life at its absolute most heart-wrenchingly beautiful. And the music! Your Lie is a tour-de-force of classical greats, and love and care is given to portraying and animating the instruments that produce it. There’s some 3D wizardry at work here, which normally rubs me the wrong way, but I think the complicated workings of playing such intricate piano pieces couldn’t be served any other way. Like everything else, every performance is rife with tension as the show’s characters struggle to command the music to their will. These are not mere pieces for a passive audience, but a powerful energy that can traverse time and space—to send a message that the performers desperately hope will reach and be understood. Even the audience listens with dramatic intensity, noting every sway of the performer’s will and even commenting with the musical equivalent of “His power level is over NINE-THOUUUSANND!”

And the music! Your Lie is a tour-de-force of classical greats, and love and care is given to portraying and animating the instruments that produce it. There’s some 3D wizardry at work here, which normally rubs me the wrong way, but I think the complicated workings of playing such intricate piano pieces couldn’t be served any other way. Like everything else, every performance is rife with tension as the show’s characters struggle to command the music to their will. These are not mere pieces for a passive audience, but a powerful energy that can traverse time and space—to send a message that the performers desperately hope will reach and be understood. Even the audience listens with dramatic intensity, noting every sway of the performer’s will and even commenting with the musical equivalent of “His power level is over NINE-THOUUUSANND!” And despite the show’s many dips into melancholy, I appreciate that Your Lie is always up front and honest about it. The show’s main “twist”—if you can really call it that—is telegraphed so early and often that its reveal doesn’t feel like an ambush. The show’s drive for emotion never feels contrived or unfair. In fact, I think the real lie in Your Lie in April is the one you tell yourself. Until the show’s tear-jerking finale, I found myself hoping against hope that, perhaps, another resolution was possible.

And despite the show’s many dips into melancholy, I appreciate that Your Lie is always up front and honest about it. The show’s main “twist”—if you can really call it that—is telegraphed so early and often that its reveal doesn’t feel like an ambush. The show’s drive for emotion never feels contrived or unfair. In fact, I think the real lie in Your Lie in April is the one you tell yourself. Until the show’s tear-jerking finale, I found myself hoping against hope that, perhaps, another resolution was possible.

When a performer—whether that’s a pianist, a singer, or even a stand-up comedian—gets on the stage, they are immediate faced by their audience. Sometimes, the entire audience matters. Other times, it is only a choice few, be it trying to capture the heart of a loved one or impressing the hard-nosed judge. Whatever the case, the audience is given a DN based on how hard they are to impress. A fun night out at karaoke is prone to require a paltry 4 or 6, while world competitions may require 12—and beyond!

When a performer—whether that’s a pianist, a singer, or even a stand-up comedian—gets on the stage, they are immediate faced by their audience. Sometimes, the entire audience matters. Other times, it is only a choice few, be it trying to capture the heart of a loved one or impressing the hard-nosed judge. Whatever the case, the audience is given a DN based on how hard they are to impress. A fun night out at karaoke is prone to require a paltry 4 or 6, while world competitions may require 12—and beyond!

Speaking of music, readers, do you have a favorite anime with that subject as its focus? How about your favorite anime soundtrack? Tell me about it in the comments! Also, if you’d like to support this blog, consider purchasing Your Lie in April merchandise like

Speaking of music, readers, do you have a favorite anime with that subject as its focus? How about your favorite anime soundtrack? Tell me about it in the comments! Also, if you’d like to support this blog, consider purchasing Your Lie in April merchandise like

But Kyouma is only one half of the equation, and in short order he’s paired with Mira, a mysteriously advanced, and of course coil-powered, android that represents everything Kyouma has done his best to leave behind. It’s no secret that I love the gynoid archetype—Miho, after all, was the first character I created for OVA—and Mira is a particularly likable example. The strained relationship between the duo gives some meat to the usual robot-girl-wants-to-be-accepted-as-human plotline, and the combination of these opposites just made me fall in love with the show.

But Kyouma is only one half of the equation, and in short order he’s paired with Mira, a mysteriously advanced, and of course coil-powered, android that represents everything Kyouma has done his best to leave behind. It’s no secret that I love the gynoid archetype—Miho, after all, was the first character I created for OVA—and Mira is a particularly likable example. The strained relationship between the duo gives some meat to the usual robot-girl-wants-to-be-accepted-as-human plotline, and the combination of these opposites just made me fall in love with the show. But the pseudo-science of Dimension W isn’t what the story is about really (despite how many long expository segments are devoted to it). It’s about loss and the acceptance of loss, and about the dangers of unchecked desire, all displayed through gorgeously animated action sequences and an eclectic cast of quirky characters. Whether it’s Loser, the prolific criminal who seemingly never succeeds at stealing but has become sort of a public hero and phenomenon for it, or the delightfully bizarre competing collectors featured during the story’s final arc, or just Kyouma’s clever use of his skewer-and-cable weapons, Dimension W is just a lot of fun to look at.

But the pseudo-science of Dimension W isn’t what the story is about really (despite how many long expository segments are devoted to it). It’s about loss and the acceptance of loss, and about the dangers of unchecked desire, all displayed through gorgeously animated action sequences and an eclectic cast of quirky characters. Whether it’s Loser, the prolific criminal who seemingly never succeeds at stealing but has become sort of a public hero and phenomenon for it, or the delightfully bizarre competing collectors featured during the story’s final arc, or just Kyouma’s clever use of his skewer-and-cable weapons, Dimension W is just a lot of fun to look at.

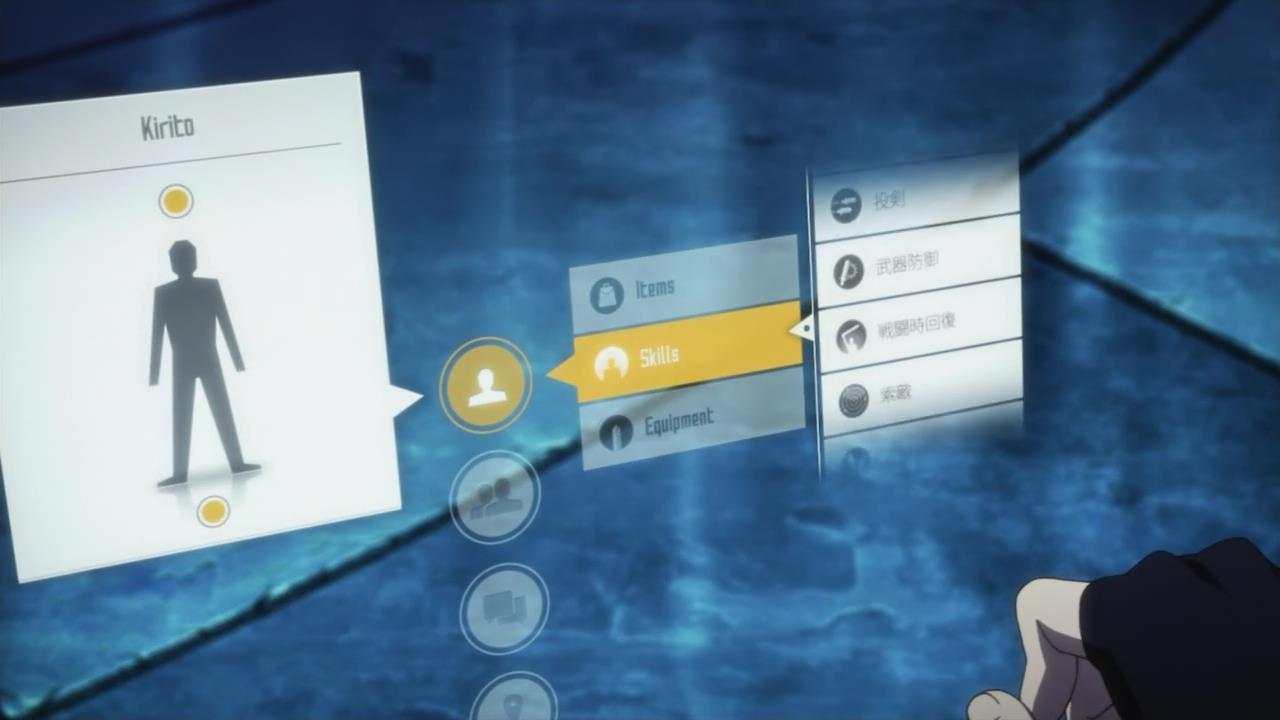

That’s because SAO is dedicated making the game world more than just window dressing. While its collection of rules and concepts are not always objectively sound if presented in a “real” MMORPG, Sword Art Online weaves its unique brand of video game logic through every layer of the narrative. Whether it’s the ebb and flow of its gorgeously animated, adrenaline-pumping battles and PvP duels, the fulfillment of quest lines and their requisite rare drops, or an entire episode devoted to a murder mystery wherein the culprit seemingly breaks the laws of SAO’s reality, the show never lets you forget that the world of Aincrad is part of a game. Even the protagonist, Kirito, has much of his golden-boy power and plot invulnerability explained by his previous experience as a beta tester. It’s great fun, and this exploration of the game itself is a piece of the puzzle .hack//SIGN glossed over in its version of the stuck in a video game tale.

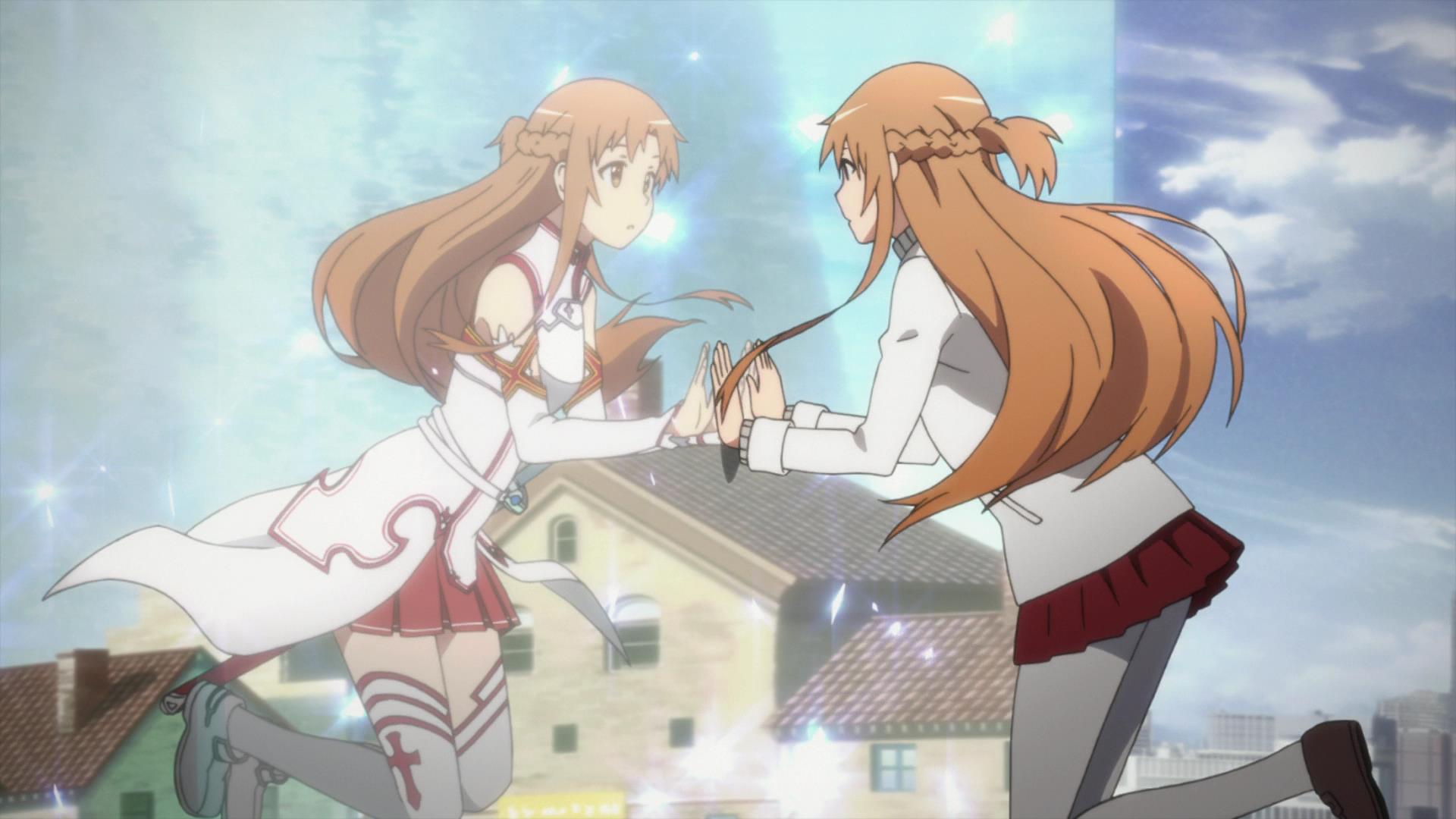

That’s because SAO is dedicated making the game world more than just window dressing. While its collection of rules and concepts are not always objectively sound if presented in a “real” MMORPG, Sword Art Online weaves its unique brand of video game logic through every layer of the narrative. Whether it’s the ebb and flow of its gorgeously animated, adrenaline-pumping battles and PvP duels, the fulfillment of quest lines and their requisite rare drops, or an entire episode devoted to a murder mystery wherein the culprit seemingly breaks the laws of SAO’s reality, the show never lets you forget that the world of Aincrad is part of a game. Even the protagonist, Kirito, has much of his golden-boy power and plot invulnerability explained by his previous experience as a beta tester. It’s great fun, and this exploration of the game itself is a piece of the puzzle .hack//SIGN glossed over in its version of the stuck in a video game tale. And Asuna, the show’s requisite waifu for Kirito, far exceeds such a label. That’s because Asuna is more than a damsel backdrop for Kirito to show off his mettle. If anything, Asuna carries the show. While Kirito has his beta test experience and a few convenient plot abilities to fall back on, Asuna’s aptitude at the game was tempered in the game itself. She is on the front-lines despite not knowing the road ahead, and it is through her own conviction and power that the day is saved at critical moments throughout the show’s first story arc.

And Asuna, the show’s requisite waifu for Kirito, far exceeds such a label. That’s because Asuna is more than a damsel backdrop for Kirito to show off his mettle. If anything, Asuna carries the show. While Kirito has his beta test experience and a few convenient plot abilities to fall back on, Asuna’s aptitude at the game was tempered in the game itself. She is on the front-lines despite not knowing the road ahead, and it is through her own conviction and power that the day is saved at critical moments throughout the show’s first story arc. That’s not to say the second arc is bad. It’s perfectly watchable, and despite fan outrage that I largely chalk up to “She’s not Asuna,” Sugaha/Leafa is cute and likeable. It just doesn’t deliver on the promise exhibited in the earlier episodes, instead falling hook, line, and sinker into the mire of expectations it so expertly cast off before.

That’s not to say the second arc is bad. It’s perfectly watchable, and despite fan outrage that I largely chalk up to “She’s not Asuna,” Sugaha/Leafa is cute and likeable. It just doesn’t deliver on the promise exhibited in the earlier episodes, instead falling hook, line, and sinker into the mire of expectations it so expertly cast off before.

This Flinch complication is inflicted in one of two ways: One is by dealing any other combat complication, which will also inflict the Flinched status. The other is reserved for enemies with large, heavy-hitting weapons or attacks. If they should ever attack a character but deal no damage, they are immediately put into the Flinched state.

This Flinch complication is inflicted in one of two ways: One is by dealing any other combat complication, which will also inflict the Flinched status. The other is reserved for enemies with large, heavy-hitting weapons or attacks. If they should ever attack a character but deal no damage, they are immediately put into the Flinched state.

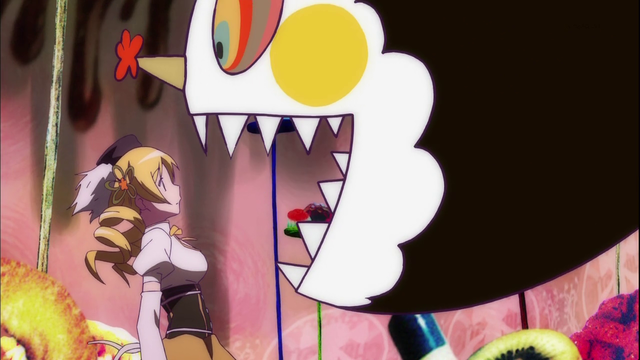

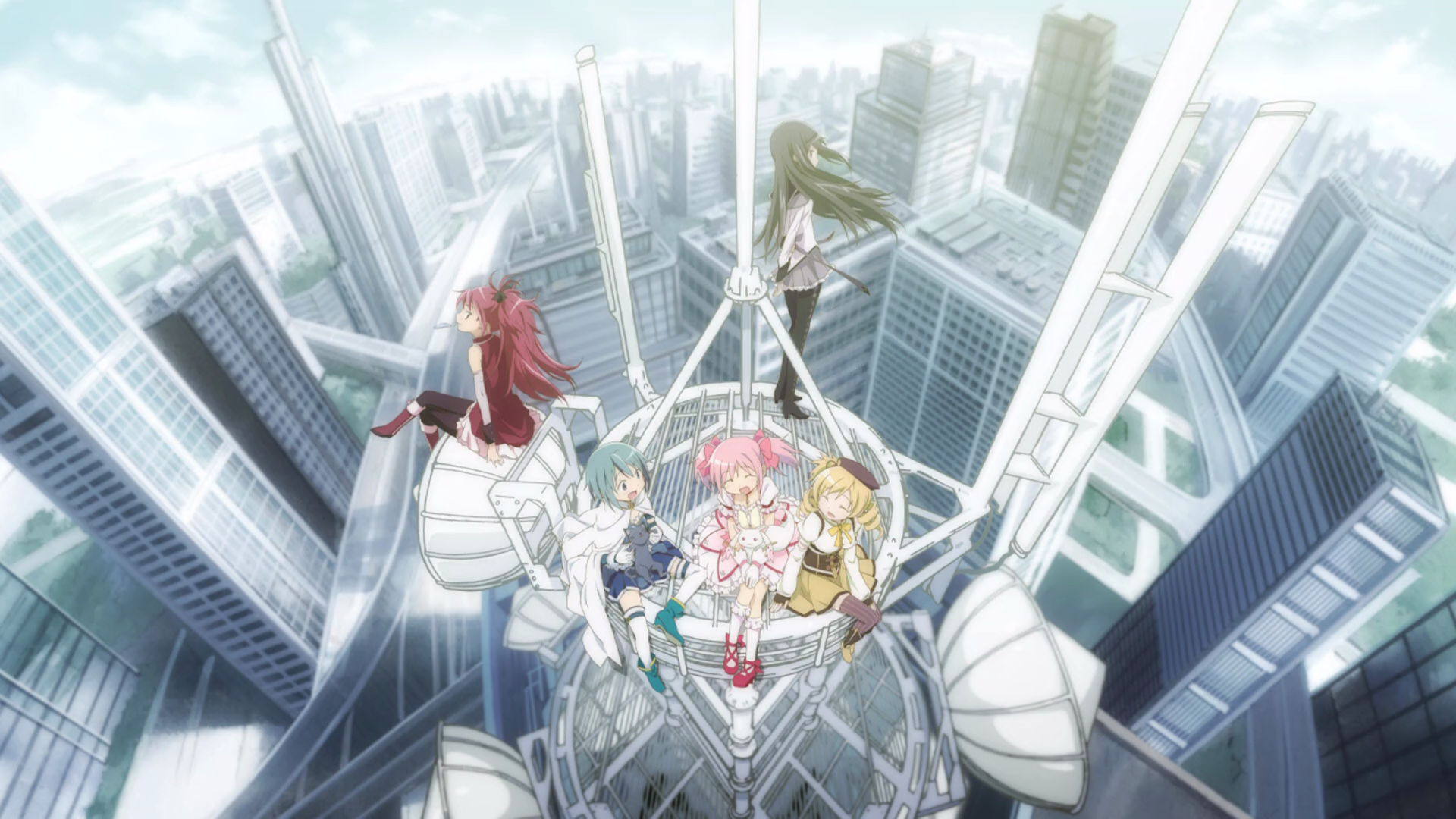

While I am loath to do any major spoiling in my overview here, I think it is a testament to the show that for all its turnarounds and revelations, it holds up to repeat viewings and—dare I say—is possibly better for it. Motivations that seemed arcane before are clear, and countless details unnoticeable the first time around are scattered throughout the narrative. And for all its slow pacing for the early part of the show, Madoka sets up what will be its biggest strength: The show really isn’t about Madoka at all. When you discover the heart of the matter, every frame becomes a cherished part of the whole.

While I am loath to do any major spoiling in my overview here, I think it is a testament to the show that for all its turnarounds and revelations, it holds up to repeat viewings and—dare I say—is possibly better for it. Motivations that seemed arcane before are clear, and countless details unnoticeable the first time around are scattered throughout the narrative. And for all its slow pacing for the early part of the show, Madoka sets up what will be its biggest strength: The show really isn’t about Madoka at all. When you discover the heart of the matter, every frame becomes a cherished part of the whole.

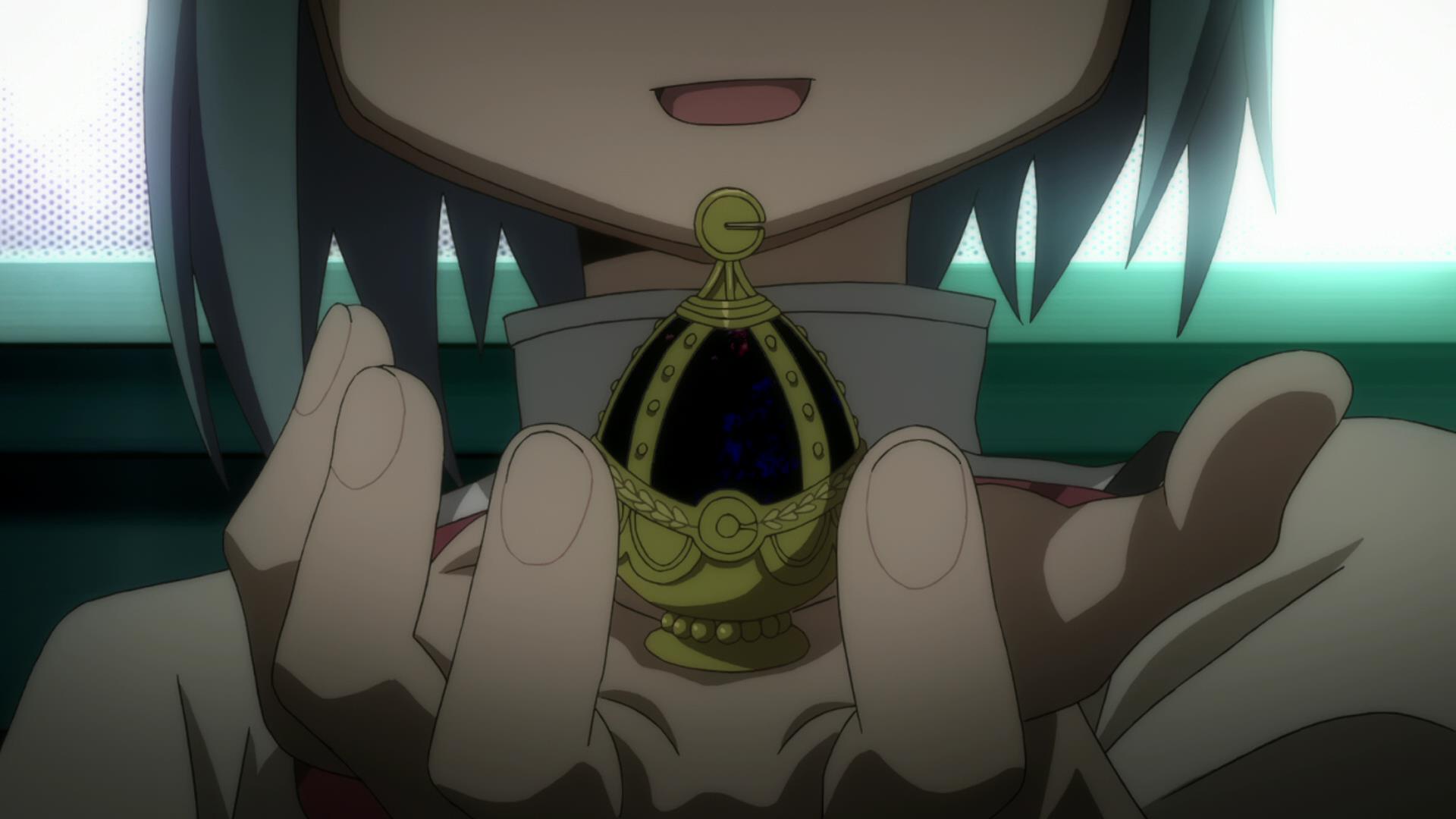

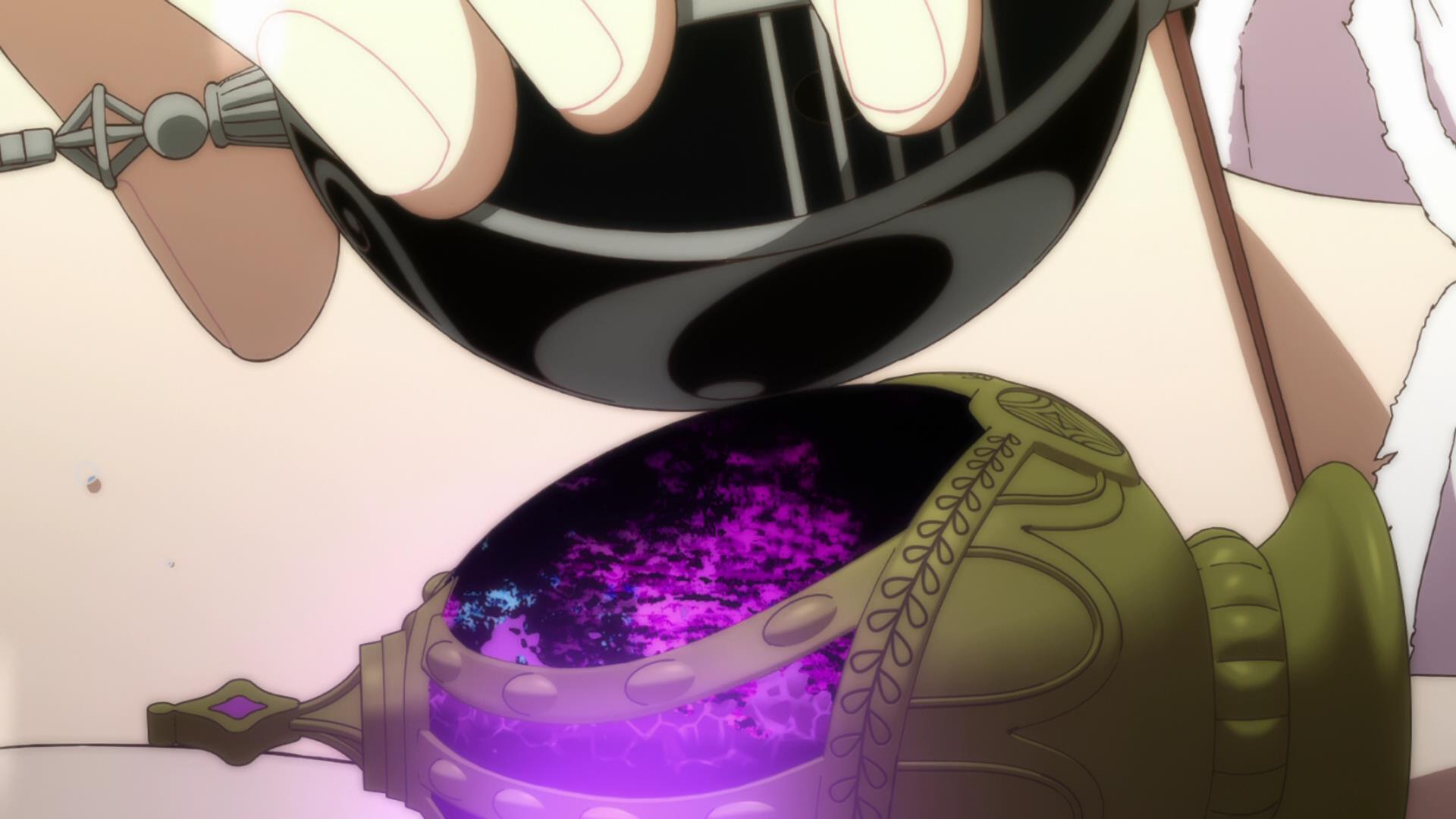

Because a magical girl’s soul lies within her gem, and the human body has become merely a shell for action, should the distance between the body and the gem grow too far, the ability to control the body is lost and it becomes effectively dead. As long as they are reunited, the magical girl can continue on as before, but if they are not…

Because a magical girl’s soul lies within her gem, and the human body has become merely a shell for action, should the distance between the body and the gem grow too far, the ability to control the body is lost and it becomes effectively dead. As long as they are reunited, the magical girl can continue on as before, but if they are not…

It’s an intriguing premise on its own, but when the death of someone close to Satoru results in him being framed for the crime, Revival kicks into overdrive and send him all the way back to 1988—to his childhood days where he and his classmates experience the abduction and death of fellow students. As an adult-minded Satoru relives his youth, he realizes that these murders may be the source of his misfortune in the present, perhaps the origin of everything, and he sets out to change the future.

It’s an intriguing premise on its own, but when the death of someone close to Satoru results in him being framed for the crime, Revival kicks into overdrive and send him all the way back to 1988—to his childhood days where he and his classmates experience the abduction and death of fellow students. As an adult-minded Satoru relives his youth, he realizes that these murders may be the source of his misfortune in the present, perhaps the origin of everything, and he sets out to change the future. This especially true since Satoru’s success in changing the future has as much to do with changing his relationships in the past as it does his detective work. His efforts to keep Kayo, the serial killer’s first victim, from being vulnerable and alone develop into much more, as they each discover the truth in each other and the insecurities he didn’t fully understand as a child. It’s not just Kayo, either, as Satoru reaches out and makes deeper, more profound connections with his core circle of friends, eventually enlisting them on his quest to thwart the dismal future.

This especially true since Satoru’s success in changing the future has as much to do with changing his relationships in the past as it does his detective work. His efforts to keep Kayo, the serial killer’s first victim, from being vulnerable and alone develop into much more, as they each discover the truth in each other and the insecurities he didn’t fully understand as a child. It’s not just Kayo, either, as Satoru reaches out and makes deeper, more profound connections with his core circle of friends, eventually enlisting them on his quest to thwart the dismal future. The show deftly juggles the murder mystery and everyday life, Satoru’s past and present, and spans of calm and drama in a way that neither ever outlives its welcome. It’s a mixture that thrives on each other, and the show’s pacing perfectly sets up the conclusion in a way that imminently satisfying. That’s not to say the show is without faults. One of the main antagonist’s characterization is embarrassingly thin; even the serial killer that serves as the catalyst for the entire story isn’t much better. But that’s okay, because the story isn’t really about them. It isn’t really even about the murder mystery. It’s about people treating each other with kindness, learning to see past the failings of ourselves and others, past the barriers we erect around us. And connect.

The show deftly juggles the murder mystery and everyday life, Satoru’s past and present, and spans of calm and drama in a way that neither ever outlives its welcome. It’s a mixture that thrives on each other, and the show’s pacing perfectly sets up the conclusion in a way that imminently satisfying. That’s not to say the show is without faults. One of the main antagonist’s characterization is embarrassingly thin; even the serial killer that serves as the catalyst for the entire story isn’t much better. But that’s okay, because the story isn’t really about them. It isn’t really even about the murder mystery. It’s about people treating each other with kindness, learning to see past the failings of ourselves and others, past the barriers we erect around us. And connect.

Revival—Time does not flow smoothly for you. When great misfortune, harm, or other danger happens around you, your life’s clock rewinds a few precious seconds, giving you a second chance to notice what has gone wrong. This awareness is not automatic, as you only know that you have jumped back into the past, not the exact reason for it. The greater your level in Revival, the more time your character rewinds backward, giving you longer to assess the situation and act upon it. Add your Revival Dice to any actions you manage to take during the span of time that you repeat. If you can’t discover the reason for the Revival (with Abilities like Perceptive or Sixth Sense) or act on them in time, the Revival and its Bonus dice end.

Revival—Time does not flow smoothly for you. When great misfortune, harm, or other danger happens around you, your life’s clock rewinds a few precious seconds, giving you a second chance to notice what has gone wrong. This awareness is not automatic, as you only know that you have jumped back into the past, not the exact reason for it. The greater your level in Revival, the more time your character rewinds backward, giving you longer to assess the situation and act upon it. Add your Revival Dice to any actions you manage to take during the span of time that you repeat. If you can’t discover the reason for the Revival (with Abilities like Perceptive or Sixth Sense) or act on them in time, the Revival and its Bonus dice end.

But Spike isn’t just sort of good at both, he’s great. And if you couldn’t create Spike with ease in OVA, then that’s as much of a litmus test as anything. With that in mind, I condensed every combat skill into an Ability called, well, Combat Skill. With one attribute, your character was adept at attacking, whatever form that takes. Sure, it flies in the face of most RPG design that routinely compartmentalize such things, but it just made things so much easier. You could still just do one thing, of course, but if you ever wanted to branch out, you weren’t punished for it.

But Spike isn’t just sort of good at both, he’s great. And if you couldn’t create Spike with ease in OVA, then that’s as much of a litmus test as anything. With that in mind, I condensed every combat skill into an Ability called, well, Combat Skill. With one attribute, your character was adept at attacking, whatever form that takes. Sure, it flies in the face of most RPG design that routinely compartmentalize such things, but it just made things so much easier. You could still just do one thing, of course, but if you ever wanted to branch out, you weren’t punished for it. While this was easily the most gratifying change to OVA, there’s a vast variety of additions and improvements that I’m also fond of. The original game’s “knockback” was split into three separate combat complications, giving more tactical options to the otherwise streamlined rules. Looking at these, I realized that I could take the same concept and apply them outside of combat, and Succeeding with Complications was born. While I won’t be foolhardy enough to claim this is an entirely new idea (Fate, if nothing else, pushes the “fail forward” concept hard), I’m really please with how neatly it fits into OVA and brings combat and out-of-combat closer together thematically.

While this was easily the most gratifying change to OVA, there’s a vast variety of additions and improvements that I’m also fond of. The original game’s “knockback” was split into three separate combat complications, giving more tactical options to the otherwise streamlined rules. Looking at these, I realized that I could take the same concept and apply them outside of combat, and Succeeding with Complications was born. While I won’t be foolhardy enough to claim this is an entirely new idea (Fate, if nothing else, pushes the “fail forward” concept hard), I’m really please with how neatly it fits into OVA and brings combat and out-of-combat closer together thematically.

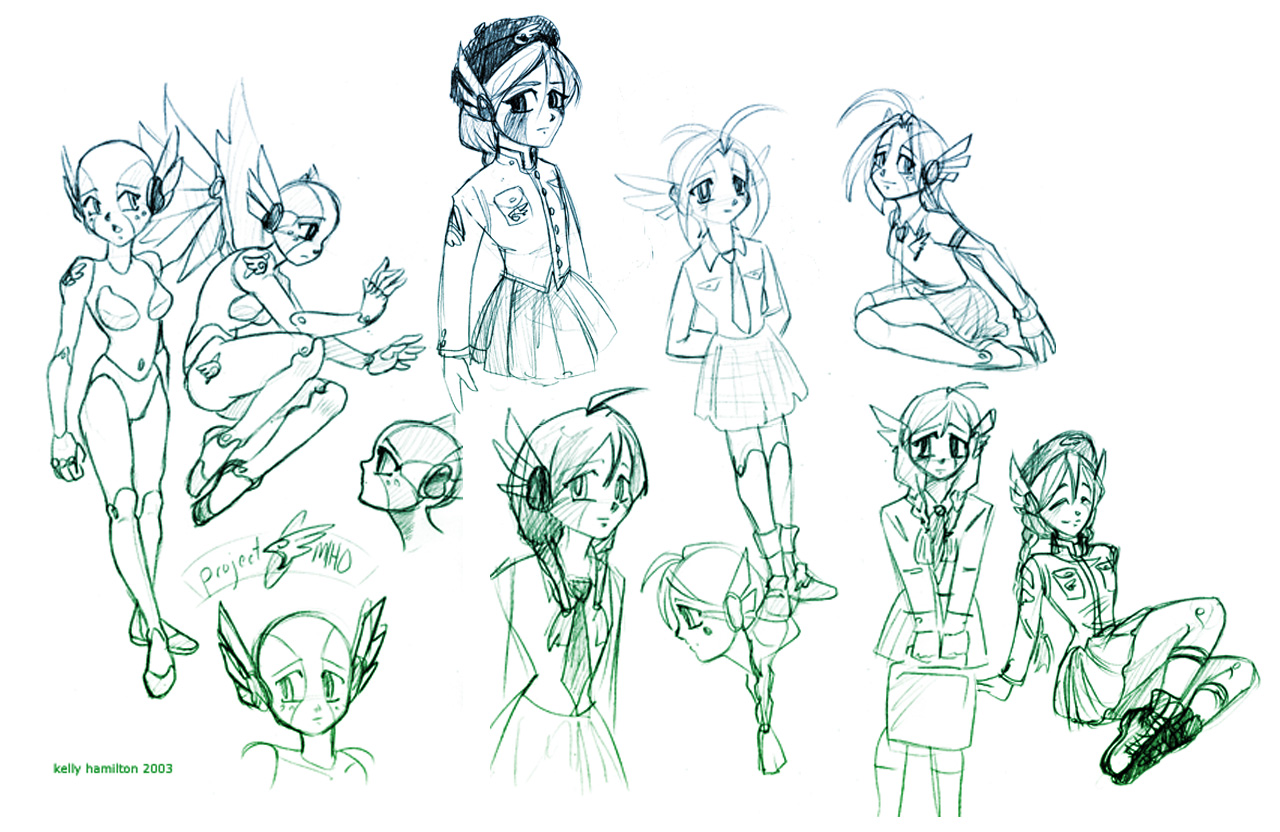

The military-inspired uniform makes its first appearance here and was used for her final design. This iconic ensemble would go on to be featured (more or less) in the revised game, despite the fact that most other character designs changed completely.

The military-inspired uniform makes its first appearance here and was used for her final design. This iconic ensemble would go on to be featured (more or less) in the revised game, despite the fact that most other character designs changed completely. Oh, and if you’re wondering about my illustrations mentioned earlier, here’s a final comparison featuring everyone’s favorite copper, Jiro.

Oh, and if you’re wondering about my illustrations mentioned earlier, here’s a final comparison featuring everyone’s favorite copper, Jiro. Slight improvement, right?

Slight improvement, right?