As much as any one show can, Evangelion seems to encompass what anime is. Towering mecha duking it out with even more massive monsters, cutesy animal mascots, catchy opening music, and two candidates for “best girl” that have engendered debates going on for two decades now.

But as the episodes go by, this begins to feel less and less true. Those marvels of mechanical might, the show’s “Eva,” are almost indescribably unsettling. The solid, purposeful movements of their super robot show forebears are replaced with agile, animalistic strides; metallic joints flex and tighten in supple, organic ways; and instead of serving solely as window to the pilot themselves, we see a robot that is alive with growls and groans and wounds that ooze and bleed.

The pilots, too, defy expectation. These are not plucky, self-assured heroes ready to save the world. They’re children, children who strive for the approval and affection of the adults around them, but find only demands and expectations in return. Anime-whipping-boy Shinji is often portrayed as a whiner by fans, but if anything, through most of the show’s run he readily submits himself to a job time and again that, rightly so, terrifies him—just so he achieve what he desires most: attention from his father.

Shinji is hardly alone in this regard. Asuka blusters and postures in an attempt to appear the self-sufficient adult in the face of a mother who abandoned her. Rei, who knows no life at all but to be used, struggles to understand relationships beyond the immutable tool dynamic forced upon her. Even characters like Misato and Ritsuko, full-grown adults, struggle with the remnants of their own childhoods and parental trauma and deal with it in flawed, self-destructive ways.

The show reveals this to us, little by little, in the guise of a monster-of-the-week show. An “Angel” shows up, bringing with it its own unique conundrum that must be solved before the episode’s end. Our youthful pilots are forced to confront their doubts and shortcomings, whether it’s Shinji’s trepidation about “getting in the robot”, his synchronizing with Asuka—and thus being forced to form an emotional connection with someone—in one of the series’ highlight episodes, or dealing with the inherent morality of being arbiters of life and death. As Evangelion goes through the motions of the genre it embodies, it deconstructs it in meaningful, interesting ways.

But no matter how many Angels there are to defeat, no matter how many tribulations must be triumphed over, what every character in the show wants, really, is to be loved—to be accepted for the flawed, broken people that they are. Even the infamous Gendo Ikari, for all his glasses flashing, finger temple-ing, abysmal parenting, is only seeking to recapture the love he has lost while failing completely to impart that same love to his son.

But as the show hurtles on to its conclusion, any semblance of careful pacing is thrown out the window. Gone are the bits and pieces of character development interspersed with tense action sequences and breath-catching moments of levity. Instead we are treated to diatribes of incomprehensible technobabble that, instead of buoying our characters’ development, threaten to overshadow them at every turn. The introduction of Kaoru, a seminal encounter in Shinji’s aspiration for acceptance, rushes through its character arc in a mere 25 minutes, something that could’ve lasted an entire season, and in doing so obliterates any chance to inspire the emotional connection it strives to impart.

And then we find ourselves reaching Evangelion’s controversial climax—the ending the franchise has spent the better part of this millennium rewriting over and over. The truth of the matter is it’s not a bad ending at all. The entire show has been building up to this moment in Shinji’s life, this monologue of introspection where Shinji really has to deal with his anxiety and depression without hiding or running away.

But the moment is buried under baffling reused animation clips and the dangling questions of the shows’ own plot. What has been Seele’s goal all along? Gendo Ikari’s? What are the Dead Sea Scrolls? What were the Angels? What is this Human Instrumentality Project introduced in the show’s eleventh hour? It’s hard to cast blame for disliking an ending that feels so woefully incomplete. But if you’re willing to write away these questions as window dressing, or supplement your viewing with a bit of research, Eva’s ending encapsulates a complete catharsis of Shinji’s struggle—and as such is a much more satisfying ending that the more explicitly explained (yet somehow even more discombobulating) End of Evangelion.

But perhaps this incompleteness is as much a part of Evangelion’s enduring appeal as its memorable characters and awe-inspired designs. As the show takes its journey from sumptuously animated straight-up action romp to avant guard stream-of-consciousness introspection, there is a spot on this crazy train for everyone. And perhaps that’s why no single end-of-the-line is ever going to appease everyone. Like Shinji, perhaps Evangelion is something we simply ask too much from.

Perhaps that’s about as fitting a legacy as you’ll get.

Evangelion and OVA

Despite the length I go to demonstrate Eva’s super-robot trappings as a frame for a story about the human condition, inevitably the first question most people will ask about representing Eva in OVA is “How do we make the mecha go boom-boom?”

The answer is pretty straightforward. None of the Evas demonstrate any specific strengths or weaknesses, and even their armaments tend to be slave to the plot as opposed to anything concretely measured or differentiated. Just stat up capable combatants with decent points in “Attack” and you’ll be hard-pressed to go wrong.

What Evangelion does bring to the table that’s inherently interesting is the Eva units almost complete lack of a self-sustaining power-source. Without being literally plugged in, Evas run out of juice within minutes. It’s a fascinating wrinkle to the Angel-fighting hijinks, and one that immediately sets Evangelion apart from other giant robot-style shows.

Racing Against the Clock

Time is relatively abstract in OVA. You won’t find passages in the text extolling that a round is ten seconds long, or that a given action chips off a discrete amount of time from a hypothetical clock. For most narrative purposes, this works just fine.

But sometimes time matters—really matters. Evangelion drives this concept home when the Evas become separated from a dedicated power source. Whether due to severed plugs, long-distance deployment, or enemy interference, as much as the Angels themselves, time is the enemy.

That’s not to say one should adopt the ten-second round or anything so pedantically concrete. Despite the explicitly defined “five minutes” of the show, the narrative beats stretch and contract to fit whatever the plot demands. It is a constraint, but an elastic one.

So instead of setting a real-world time frame, it’s more prudent to simply assign a number of “Beats.” 10 is a decent amount, but this can be expanded or reduced as the Game Master sees fit. Likewise, the Game Master can increment the clock at any time. You could do this once a round, but also consider the narrative flow of the story:

- A character completes an action that takes a step towards a goal—or prevents another from completing their own.

- A character has dealt or received a significant chunk of damage. (Ie. by inflicting/incurring the zero Health Penalty.)

- An NPC provides useful information that contributes to the current conflict.

Also certain rolls will affect the spending of Beats.

- If a character has an Amazing Success, or inflicts a complication, that action will never spend a Beat.

- If a character fails an action of importance, it will always spend a Beat. (Missing in Combat does not count.)

But the flow of time is not solely at the Game Master’s discretion or the whim of the dice. The Players can use time to their advantage, or expend more of themselves to get the job done a little faster.

- A character may spend Drama Dice (or incur a –1 Penalty) to buy off a Beat that would ordinarily be spent.

- A character may get a Drama die by spending an extra Beat.

Obviously when there are no more Beats, time has run out! Hopefully the PCs have plenty of Endurance to burn to keep that from happening!

…By the by, that whole “best girl” thing I mentioned earlier? There’s only one right answer.

Through its earnest striving to paint a picture of these emotions, though, the show often tries to tell us what to feel instead of making us feel it ourselves. Characters are a constant source of waterworks, but often their trials and tribulations are given too little time to mature, their triumphs and tragedies relegated to less than careful exposition, making the tears themselves bear the weight of the story’s emotional gravitas.

Through its earnest striving to paint a picture of these emotions, though, the show often tries to tell us what to feel instead of making us feel it ourselves. Characters are a constant source of waterworks, but often their trials and tribulations are given too little time to mature, their triumphs and tragedies relegated to less than careful exposition, making the tears themselves bear the weight of the story’s emotional gravitas. The show may be at its best, though, when we can peer more into Violet herself. While much of the time she exhibits a personality as flat as the dolls that her occupation’s name alludes to, the stark contrast amplifies her struggle to understand what it means to live a normal life. Her mechanical arms serve as a flashy, overt metaphor for her own emotional development—as she adjusts to their clumsy, unsubtle nature, so too does she shed the shell of her guarded personality…at least a little.

The show may be at its best, though, when we can peer more into Violet herself. While much of the time she exhibits a personality as flat as the dolls that her occupation’s name alludes to, the stark contrast amplifies her struggle to understand what it means to live a normal life. Her mechanical arms serve as a flashy, overt metaphor for her own emotional development—as she adjusts to their clumsy, unsubtle nature, so too does she shed the shell of her guarded personality…at least a little. Yet, we never learn how Violet’s mechanical arms work in a world otherwise devoid of such technological marvels, any more than we learn about Violet’s own origins or the source of her amazing combat ability. But these details are incidental to her journey. Sometimes all you need is a typewriter and the right words—all these exactingly fashioned, carefully wrought, painstakingly perfected words to understand what it means when we say,

Yet, we never learn how Violet’s mechanical arms work in a world otherwise devoid of such technological marvels, any more than we learn about Violet’s own origins or the source of her amazing combat ability. But these details are incidental to her journey. Sometimes all you need is a typewriter and the right words—all these exactingly fashioned, carefully wrought, painstakingly perfected words to understand what it means when we say,

When it comes time to write the letter, the Auto Memory Doll rolls all dice that apply. At its simplest, this can be covered by Unique Ability: Auto Memory Doll, but it can also be split up into different sub-facets, like Grammar, Empathy, and Poetry. On the other hand, you can simply use the Abilities already in OVA that apply.

When it comes time to write the letter, the Auto Memory Doll rolls all dice that apply. At its simplest, this can be covered by Unique Ability: Auto Memory Doll, but it can also be split up into different sub-facets, like Grammar, Empathy, and Poetry. On the other hand, you can simply use the Abilities already in OVA that apply.

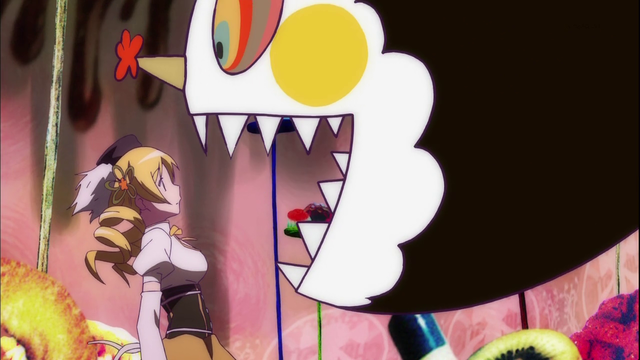

Her FranXX is nimble and bestial as we watch her fight. The klaxosaur is alien and frightening, immediately casting an ominous shadow as we stare death in the face. But Zero Two cannot defeat it alone. Despite his past failures, despite Zero Two’s fearsome reputation, Hiro volunteers to pilot with her. Sealing this pact with a kiss, Zero Two pilots with her “darling,” and we see the true form of the FranXX as it transforms…into a shapely, saucer-eyed battle bot.

Her FranXX is nimble and bestial as we watch her fight. The klaxosaur is alien and frightening, immediately casting an ominous shadow as we stare death in the face. But Zero Two cannot defeat it alone. Despite his past failures, despite Zero Two’s fearsome reputation, Hiro volunteers to pilot with her. Sealing this pact with a kiss, Zero Two pilots with her “darling,” and we see the true form of the FranXX as it transforms…into a shapely, saucer-eyed battle bot. Okay, okay, so far we’ve pretty much set up the exact plot line I expected, but as Darling continues on, it passes through phases of high school comedy, monster-of-the-week spectacular, fanservice vehicle, post-apocalyptic drama, sci-fi conspiracy epic, and well beyond. Just like the visual clash of the monstrous leonine FranXX and its girlish true form, the show is surprising and mercurial. At times, it’s as if Darling in the FranXX is never quite sure what show it wants to be. But yet, as we follow along with the adventures of Squad 13, all of these permutations, nigh haphazard as they are, fit perfectly with the show’s central theme. Darling is an exploration of what it means to grow up and all of the baggage of uncertainty that entails. Faced with a world that has largely left emotion and individuality behind, the kids are put at an even further disadvantage as they explore not just what it means to become an adult, but what it means to be human. (Even the rather…provocative…poses the pilots take in their FranXX is more than just cheap fanservice, but an overt metaphor for the relationships humanity has left behind.)

Okay, okay, so far we’ve pretty much set up the exact plot line I expected, but as Darling continues on, it passes through phases of high school comedy, monster-of-the-week spectacular, fanservice vehicle, post-apocalyptic drama, sci-fi conspiracy epic, and well beyond. Just like the visual clash of the monstrous leonine FranXX and its girlish true form, the show is surprising and mercurial. At times, it’s as if Darling in the FranXX is never quite sure what show it wants to be. But yet, as we follow along with the adventures of Squad 13, all of these permutations, nigh haphazard as they are, fit perfectly with the show’s central theme. Darling is an exploration of what it means to grow up and all of the baggage of uncertainty that entails. Faced with a world that has largely left emotion and individuality behind, the kids are put at an even further disadvantage as they explore not just what it means to become an adult, but what it means to be human. (Even the rather…provocative…poses the pilots take in their FranXX is more than just cheap fanservice, but an overt metaphor for the relationships humanity has left behind.) “What it means to be human” is a topic I put forth as a central tenet of anime in the “Telling Anime Stories” section of OVA, so it’s not exactly surprising to see it here. Yet Darling goes further than that. What does it mean to be an adult, when you’ve been told nothing about your future? What does it mean to love, when you don’t even know what a kiss is? What does it mean to be alive, when all you’ve been told how to do is fight…and die? Our heroes grapple with this and more as they strive to make a place for themselves in, and even save, this world. They have to define what they mean to each other, and what it means to mean something to each other, as they wrestle with love and unrequited love and what future they can hope for themselves beyond the culling of Klaxosaurs.

“What it means to be human” is a topic I put forth as a central tenet of anime in the “Telling Anime Stories” section of OVA, so it’s not exactly surprising to see it here. Yet Darling goes further than that. What does it mean to be an adult, when you’ve been told nothing about your future? What does it mean to love, when you don’t even know what a kiss is? What does it mean to be alive, when all you’ve been told how to do is fight…and die? Our heroes grapple with this and more as they strive to make a place for themselves in, and even save, this world. They have to define what they mean to each other, and what it means to mean something to each other, as they wrestle with love and unrequited love and what future they can hope for themselves beyond the culling of Klaxosaurs. These questions are difficult enough for the show’s young protagonists, but take on new nuances when applied to Zero Two. Being born from Klaxosaur blood, she is immediately “othered” despite her unparalleled ability to fight the Klaxosaurs themselves. Like Squad 13, she is valued for this prowess alone, but carries the extra burden of being a quote-unquote monster. As she strives along a course that she believes will bring her closer to being human, the real question becomes less “What does it mean to be human?” and more “what makes it so easy to define a thing we don’t understand as monstrous?”

These questions are difficult enough for the show’s young protagonists, but take on new nuances when applied to Zero Two. Being born from Klaxosaur blood, she is immediately “othered” despite her unparalleled ability to fight the Klaxosaurs themselves. Like Squad 13, she is valued for this prowess alone, but carries the extra burden of being a quote-unquote monster. As she strives along a course that she believes will bring her closer to being human, the real question becomes less “What does it mean to be human?” and more “what makes it so easy to define a thing we don’t understand as monstrous?” And as the characters become more confident, discover not the “right” answer to these questions but the answer they have discovered for themselves, Darling in the FranXX too matures into a show quite unlike its beginnings. This rapid evolution in the last third or so of the series was understandably divisive among fans, and you’ll see a great many discourses on how the show plummets once it reaches its endgame. But in the end, FranXX becoming something you didn’t expect—finding for itself its own definition of what it should be—is as good a metaphor for adulthood as anything. And even as the show rushes forth to this conclusion, abandoning the shackles of its youth with such speed that it stumbles over countless hurdles of exposition and casts aside almost entirely the world-building it has spent so much time developing on its way to the stars…

And as the characters become more confident, discover not the “right” answer to these questions but the answer they have discovered for themselves, Darling in the FranXX too matures into a show quite unlike its beginnings. This rapid evolution in the last third or so of the series was understandably divisive among fans, and you’ll see a great many discourses on how the show plummets once it reaches its endgame. But in the end, FranXX becoming something you didn’t expect—finding for itself its own definition of what it should be—is as good a metaphor for adulthood as anything. And even as the show rushes forth to this conclusion, abandoning the shackles of its youth with such speed that it stumbles over countless hurdles of exposition and casts aside almost entirely the world-building it has spent so much time developing on its way to the stars…

While ostensibly it is the stamen that pilots the FranXX, true effectiveness in battle requires open communication and compatibility between both FranXX pilots. Much like determining the Paracapacity score, both Players roll their Pilot dice when taking actions with the FranXX and determine their results as a combination of their dice. Either Player can choose the FranXX’s action for the turn, but in the case of disagreement, the stamen’s preference always takes precedence.

While ostensibly it is the stamen that pilots the FranXX, true effectiveness in battle requires open communication and compatibility between both FranXX pilots. Much like determining the Paracapacity score, both Players roll their Pilot dice when taking actions with the FranXX and determine their results as a combination of their dice. Either Player can choose the FranXX’s action for the turn, but in the case of disagreement, the stamen’s preference always takes precedence. Zero Two, and perhaps any pilot with Klaxosaur blood, can pilot in Stampede Mode indefinitely without this Endurance drain. However, without the stamen’s Pilot dice, the FranXX is still demonstratively less effective.

Zero Two, and perhaps any pilot with Klaxosaur blood, can pilot in Stampede Mode indefinitely without this Endurance drain. However, without the stamen’s Pilot dice, the FranXX is still demonstratively less effective.

Fittingly, Your Lie in April is possibly the prettiest anime I’ve ever watched. Almost every frame is, well, frame-able, with enough cherry blossoms dancing by to fill one of the show’s many musical venues to capacity. It’s somewhat telling that the narrative skips through summer in quick tempo in order to portray similar feats of ambiance and beauty with the falling leaves of autumn. It would be easy to say that Your Lie is too pretty for its own good, shoveling in the sakura until nothing really stands out. But that’s where the show’s most surprising, and most brilliant, juxtaposition comes in. Despite weaving a tale traversing the depths of human feeling, the show breaks up the heaviness with full-on bouts of comedy. Characters super-deform, light on fire, human torpedo each other, and otherwise elicit the kind of silliness that, at first, seems out of place. But it’s this constant reminder of levity that keeps the show from becoming a mirthless slog.

Fittingly, Your Lie in April is possibly the prettiest anime I’ve ever watched. Almost every frame is, well, frame-able, with enough cherry blossoms dancing by to fill one of the show’s many musical venues to capacity. It’s somewhat telling that the narrative skips through summer in quick tempo in order to portray similar feats of ambiance and beauty with the falling leaves of autumn. It would be easy to say that Your Lie is too pretty for its own good, shoveling in the sakura until nothing really stands out. But that’s where the show’s most surprising, and most brilliant, juxtaposition comes in. Despite weaving a tale traversing the depths of human feeling, the show breaks up the heaviness with full-on bouts of comedy. Characters super-deform, light on fire, human torpedo each other, and otherwise elicit the kind of silliness that, at first, seems out of place. But it’s this constant reminder of levity that keeps the show from becoming a mirthless slog. Calling Your Lie in April a realistic exploration of the human condition is a stretch. As they struggle with love and loss, most of its fourteen-year-old cast spout poetic treatises and wax nostalgia like middle-aged wordsmiths, but that’s okay. Lie is like the music it so throughly admires throughout the show. It is an idealized form of expression, carefully crafted to elicit the strongest emotional response. Whereas Erased celebrated the every day with its loving vignettes, Your Lie in April exalts it, creating a tapestry of the slice-of-life at its absolute most heart-wrenchingly beautiful.

Calling Your Lie in April a realistic exploration of the human condition is a stretch. As they struggle with love and loss, most of its fourteen-year-old cast spout poetic treatises and wax nostalgia like middle-aged wordsmiths, but that’s okay. Lie is like the music it so throughly admires throughout the show. It is an idealized form of expression, carefully crafted to elicit the strongest emotional response. Whereas Erased celebrated the every day with its loving vignettes, Your Lie in April exalts it, creating a tapestry of the slice-of-life at its absolute most heart-wrenchingly beautiful. And the music! Your Lie is a tour-de-force of classical greats, and love and care is given to portraying and animating the instruments that produce it. There’s some 3D wizardry at work here, which normally rubs me the wrong way, but I think the complicated workings of playing such intricate piano pieces couldn’t be served any other way. Like everything else, every performance is rife with tension as the show’s characters struggle to command the music to their will. These are not mere pieces for a passive audience, but a powerful energy that can traverse time and space—to send a message that the performers desperately hope will reach and be understood. Even the audience listens with dramatic intensity, noting every sway of the performer’s will and even commenting with the musical equivalent of “His power level is over NINE-THOUUUSANND!”

And the music! Your Lie is a tour-de-force of classical greats, and love and care is given to portraying and animating the instruments that produce it. There’s some 3D wizardry at work here, which normally rubs me the wrong way, but I think the complicated workings of playing such intricate piano pieces couldn’t be served any other way. Like everything else, every performance is rife with tension as the show’s characters struggle to command the music to their will. These are not mere pieces for a passive audience, but a powerful energy that can traverse time and space—to send a message that the performers desperately hope will reach and be understood. Even the audience listens with dramatic intensity, noting every sway of the performer’s will and even commenting with the musical equivalent of “His power level is over NINE-THOUUUSANND!” And despite the show’s many dips into melancholy, I appreciate that Your Lie is always up front and honest about it. The show’s main “twist”—if you can really call it that—is telegraphed so early and often that its reveal doesn’t feel like an ambush. The show’s drive for emotion never feels contrived or unfair. In fact, I think the real lie in Your Lie in April is the one you tell yourself. Until the show’s tear-jerking finale, I found myself hoping against hope that, perhaps, another resolution was possible.

And despite the show’s many dips into melancholy, I appreciate that Your Lie is always up front and honest about it. The show’s main “twist”—if you can really call it that—is telegraphed so early and often that its reveal doesn’t feel like an ambush. The show’s drive for emotion never feels contrived or unfair. In fact, I think the real lie in Your Lie in April is the one you tell yourself. Until the show’s tear-jerking finale, I found myself hoping against hope that, perhaps, another resolution was possible.

When a performer—whether that’s a pianist, a singer, or even a stand-up comedian—gets on the stage, they are immediate faced by their audience. Sometimes, the entire audience matters. Other times, it is only a choice few, be it trying to capture the heart of a loved one or impressing the hard-nosed judge. Whatever the case, the audience is given a DN based on how hard they are to impress. A fun night out at karaoke is prone to require a paltry 4 or 6, while world competitions may require 12—and beyond!

When a performer—whether that’s a pianist, a singer, or even a stand-up comedian—gets on the stage, they are immediate faced by their audience. Sometimes, the entire audience matters. Other times, it is only a choice few, be it trying to capture the heart of a loved one or impressing the hard-nosed judge. Whatever the case, the audience is given a DN based on how hard they are to impress. A fun night out at karaoke is prone to require a paltry 4 or 6, while world competitions may require 12—and beyond!

Speaking of music, readers, do you have a favorite anime with that subject as its focus? How about your favorite anime soundtrack? Tell me about it in the comments! Also, if you’d like to support this blog, consider purchasing Your Lie in April merchandise like

Speaking of music, readers, do you have a favorite anime with that subject as its focus? How about your favorite anime soundtrack? Tell me about it in the comments! Also, if you’d like to support this blog, consider purchasing Your Lie in April merchandise like

But Kyouma is only one half of the equation, and in short order he’s paired with Mira, a mysteriously advanced, and of course coil-powered, android that represents everything Kyouma has done his best to leave behind. It’s no secret that I love the gynoid archetype—Miho, after all, was the first character I created for OVA—and Mira is a particularly likable example. The strained relationship between the duo gives some meat to the usual robot-girl-wants-to-be-accepted-as-human plotline, and the combination of these opposites just made me fall in love with the show.

But Kyouma is only one half of the equation, and in short order he’s paired with Mira, a mysteriously advanced, and of course coil-powered, android that represents everything Kyouma has done his best to leave behind. It’s no secret that I love the gynoid archetype—Miho, after all, was the first character I created for OVA—and Mira is a particularly likable example. The strained relationship between the duo gives some meat to the usual robot-girl-wants-to-be-accepted-as-human plotline, and the combination of these opposites just made me fall in love with the show. But the pseudo-science of Dimension W isn’t what the story is about really (despite how many long expository segments are devoted to it). It’s about loss and the acceptance of loss, and about the dangers of unchecked desire, all displayed through gorgeously animated action sequences and an eclectic cast of quirky characters. Whether it’s Loser, the prolific criminal who seemingly never succeeds at stealing but has become sort of a public hero and phenomenon for it, or the delightfully bizarre competing collectors featured during the story’s final arc, or just Kyouma’s clever use of his skewer-and-cable weapons, Dimension W is just a lot of fun to look at.

But the pseudo-science of Dimension W isn’t what the story is about really (despite how many long expository segments are devoted to it). It’s about loss and the acceptance of loss, and about the dangers of unchecked desire, all displayed through gorgeously animated action sequences and an eclectic cast of quirky characters. Whether it’s Loser, the prolific criminal who seemingly never succeeds at stealing but has become sort of a public hero and phenomenon for it, or the delightfully bizarre competing collectors featured during the story’s final arc, or just Kyouma’s clever use of his skewer-and-cable weapons, Dimension W is just a lot of fun to look at.

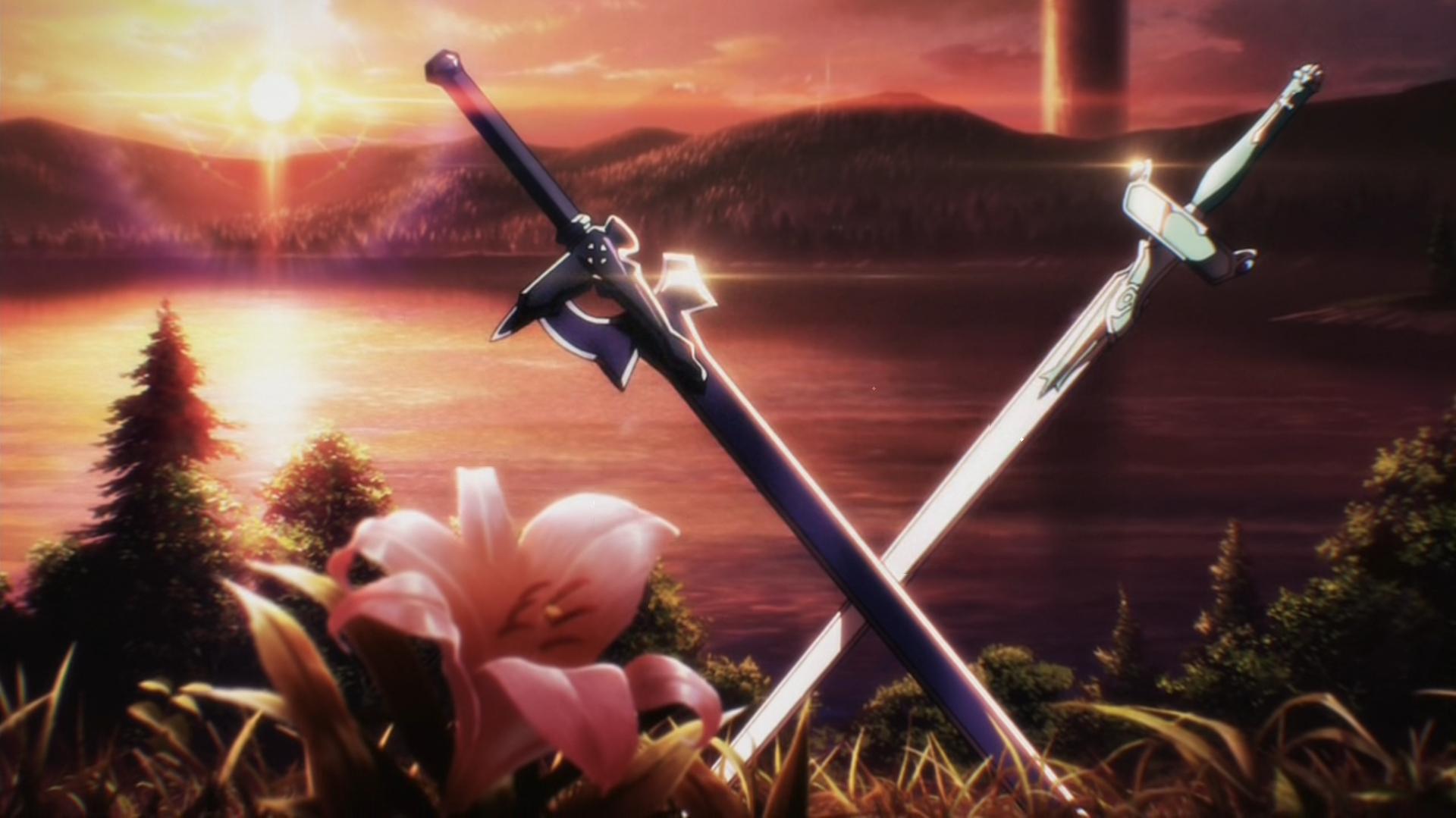

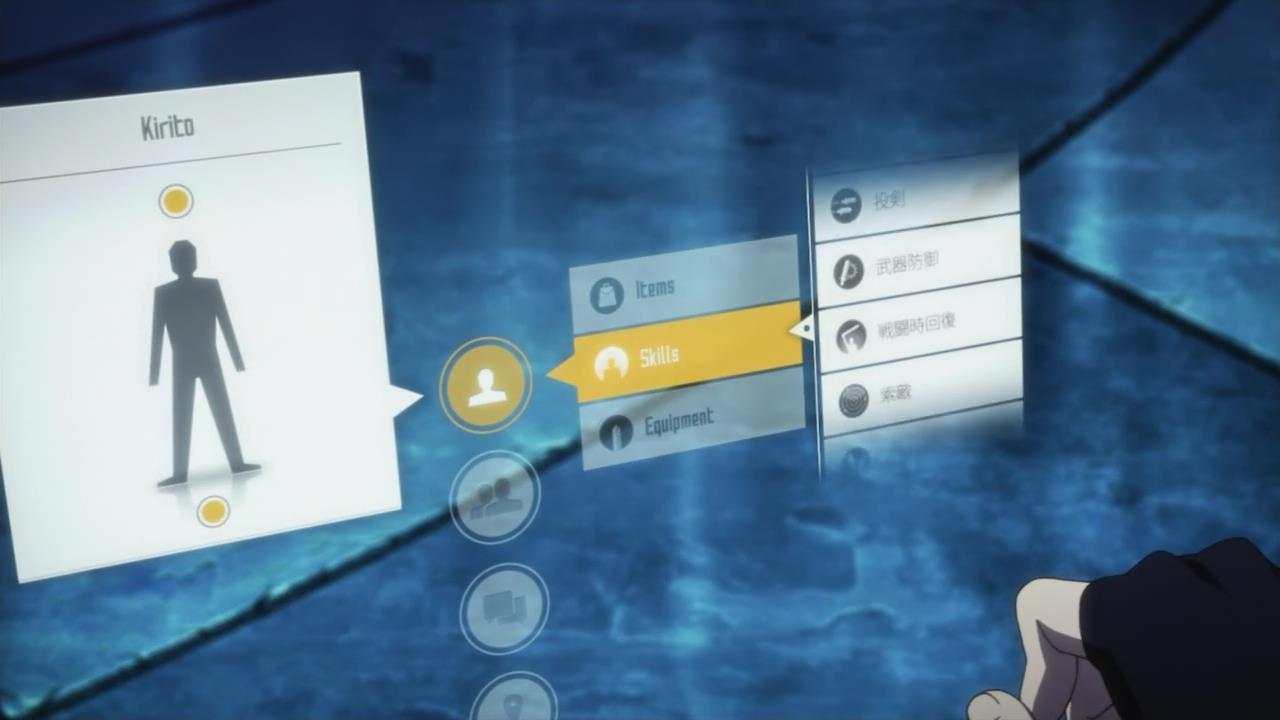

That’s because SAO is dedicated making the game world more than just window dressing. While its collection of rules and concepts are not always objectively sound if presented in a “real” MMORPG, Sword Art Online weaves its unique brand of video game logic through every layer of the narrative. Whether it’s the ebb and flow of its gorgeously animated, adrenaline-pumping battles and PvP duels, the fulfillment of quest lines and their requisite rare drops, or an entire episode devoted to a murder mystery wherein the culprit seemingly breaks the laws of SAO’s reality, the show never lets you forget that the world of Aincrad is part of a game. Even the protagonist, Kirito, has much of his golden-boy power and plot invulnerability explained by his previous experience as a beta tester. It’s great fun, and this exploration of the game itself is a piece of the puzzle .hack//SIGN glossed over in its version of the stuck in a video game tale.

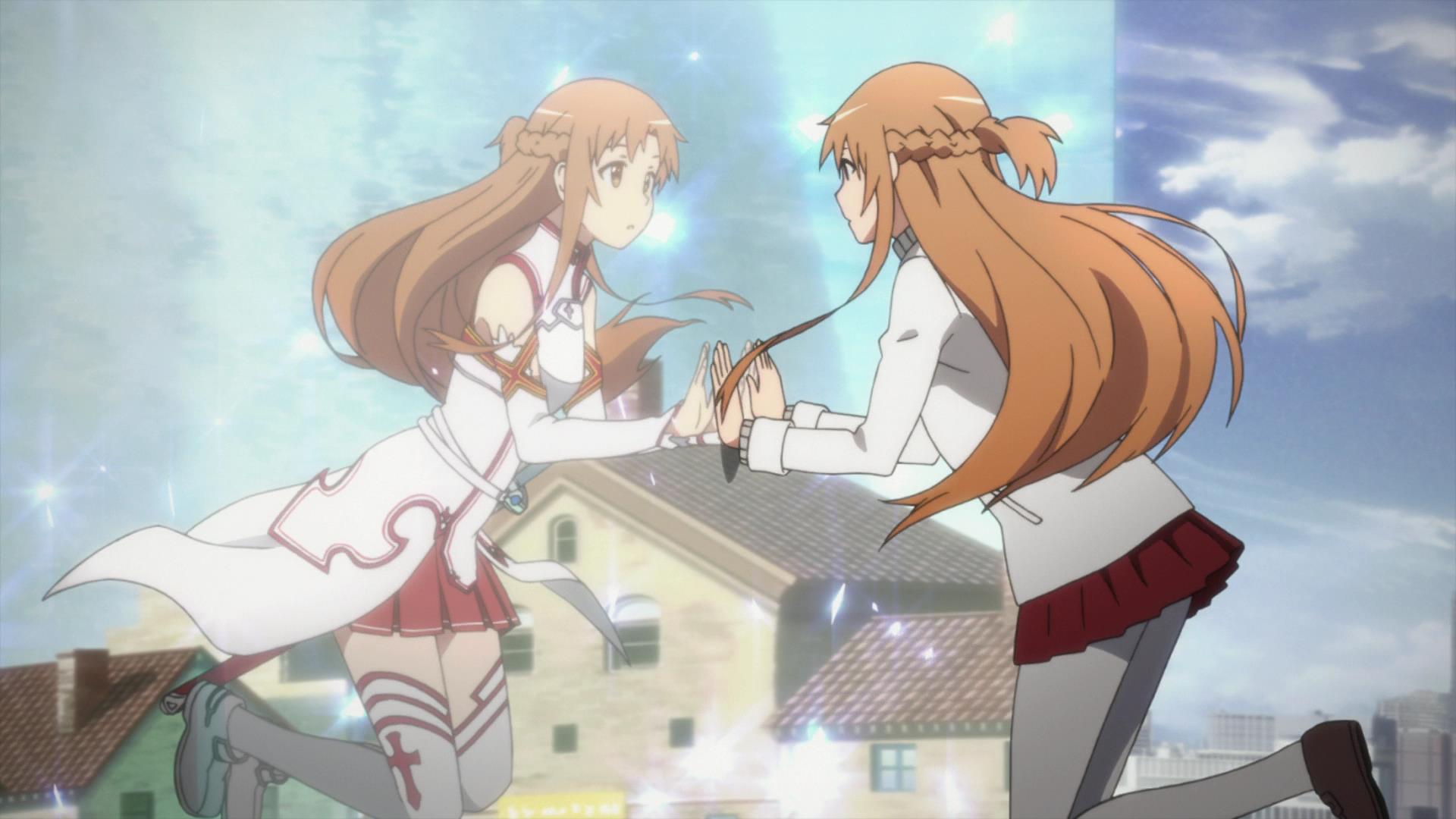

That’s because SAO is dedicated making the game world more than just window dressing. While its collection of rules and concepts are not always objectively sound if presented in a “real” MMORPG, Sword Art Online weaves its unique brand of video game logic through every layer of the narrative. Whether it’s the ebb and flow of its gorgeously animated, adrenaline-pumping battles and PvP duels, the fulfillment of quest lines and their requisite rare drops, or an entire episode devoted to a murder mystery wherein the culprit seemingly breaks the laws of SAO’s reality, the show never lets you forget that the world of Aincrad is part of a game. Even the protagonist, Kirito, has much of his golden-boy power and plot invulnerability explained by his previous experience as a beta tester. It’s great fun, and this exploration of the game itself is a piece of the puzzle .hack//SIGN glossed over in its version of the stuck in a video game tale. And Asuna, the show’s requisite waifu for Kirito, far exceeds such a label. That’s because Asuna is more than a damsel backdrop for Kirito to show off his mettle. If anything, Asuna carries the show. While Kirito has his beta test experience and a few convenient plot abilities to fall back on, Asuna’s aptitude at the game was tempered in the game itself. She is on the front-lines despite not knowing the road ahead, and it is through her own conviction and power that the day is saved at critical moments throughout the show’s first story arc.

And Asuna, the show’s requisite waifu for Kirito, far exceeds such a label. That’s because Asuna is more than a damsel backdrop for Kirito to show off his mettle. If anything, Asuna carries the show. While Kirito has his beta test experience and a few convenient plot abilities to fall back on, Asuna’s aptitude at the game was tempered in the game itself. She is on the front-lines despite not knowing the road ahead, and it is through her own conviction and power that the day is saved at critical moments throughout the show’s first story arc. That’s not to say the second arc is bad. It’s perfectly watchable, and despite fan outrage that I largely chalk up to “She’s not Asuna,” Sugaha/Leafa is cute and likeable. It just doesn’t deliver on the promise exhibited in the earlier episodes, instead falling hook, line, and sinker into the mire of expectations it so expertly cast off before.

That’s not to say the second arc is bad. It’s perfectly watchable, and despite fan outrage that I largely chalk up to “She’s not Asuna,” Sugaha/Leafa is cute and likeable. It just doesn’t deliver on the promise exhibited in the earlier episodes, instead falling hook, line, and sinker into the mire of expectations it so expertly cast off before.

This Flinch complication is inflicted in one of two ways: One is by dealing any other combat complication, which will also inflict the Flinched status. The other is reserved for enemies with large, heavy-hitting weapons or attacks. If they should ever attack a character but deal no damage, they are immediately put into the Flinched state.

This Flinch complication is inflicted in one of two ways: One is by dealing any other combat complication, which will also inflict the Flinched status. The other is reserved for enemies with large, heavy-hitting weapons or attacks. If they should ever attack a character but deal no damage, they are immediately put into the Flinched state.

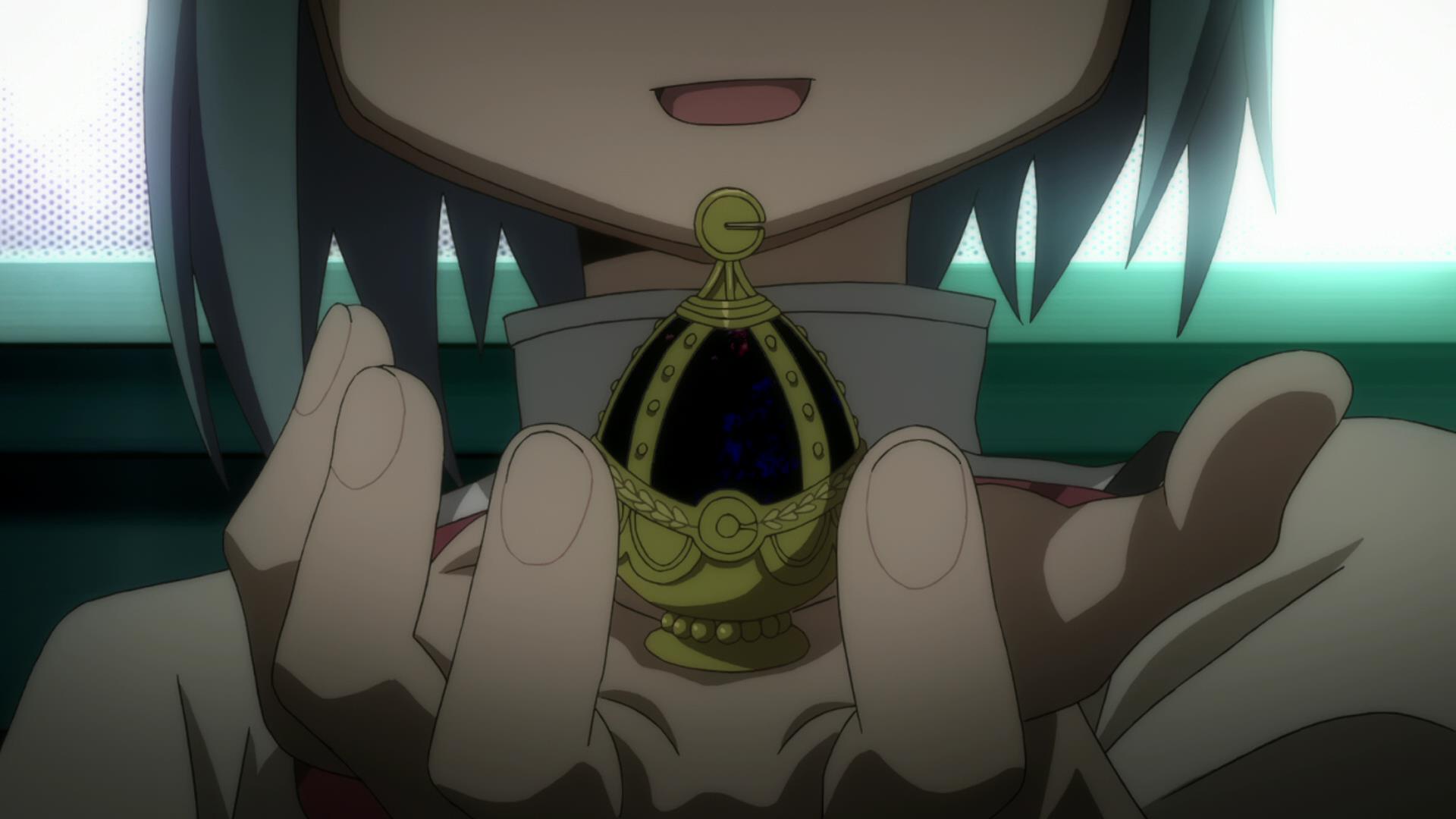

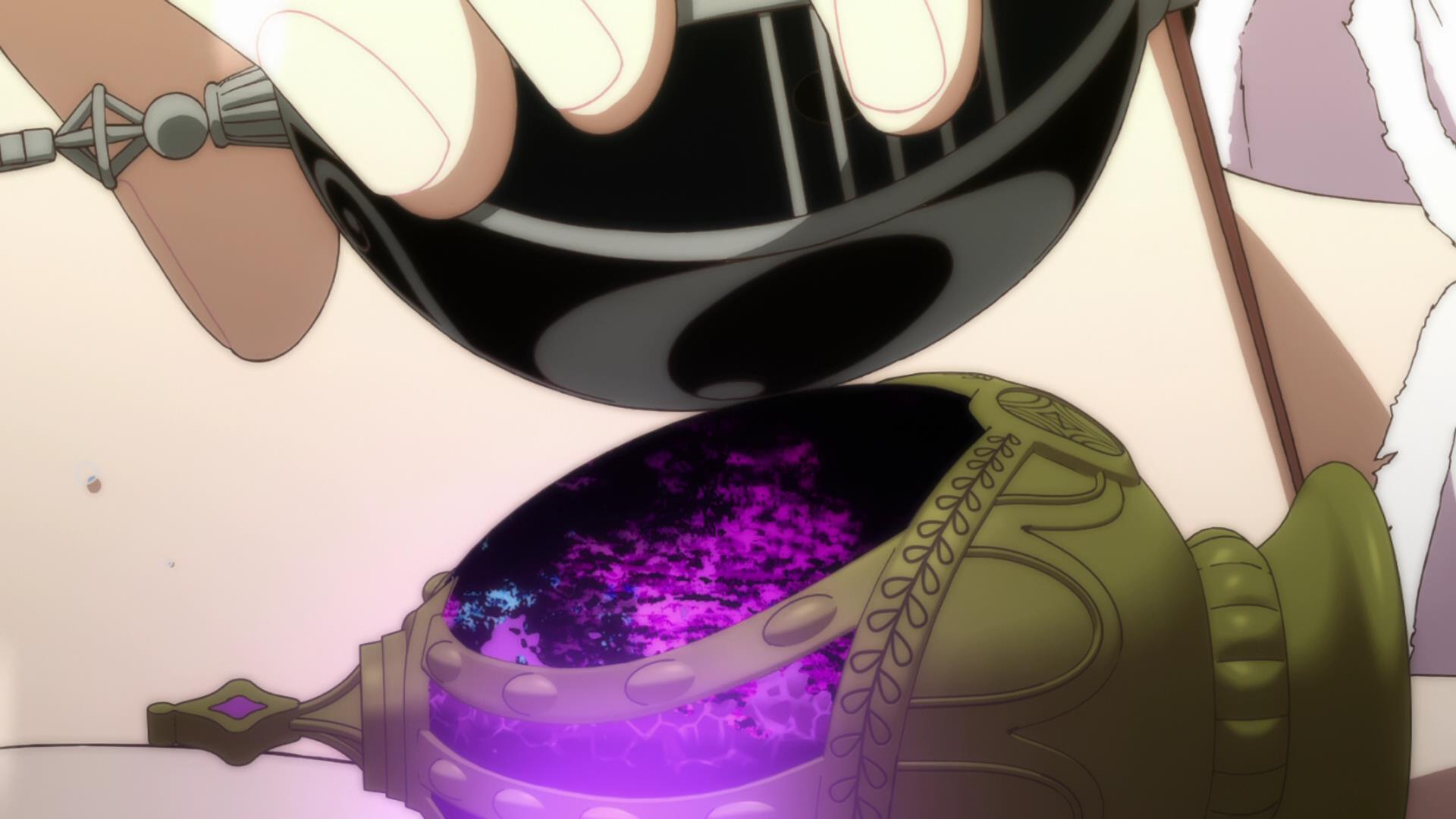

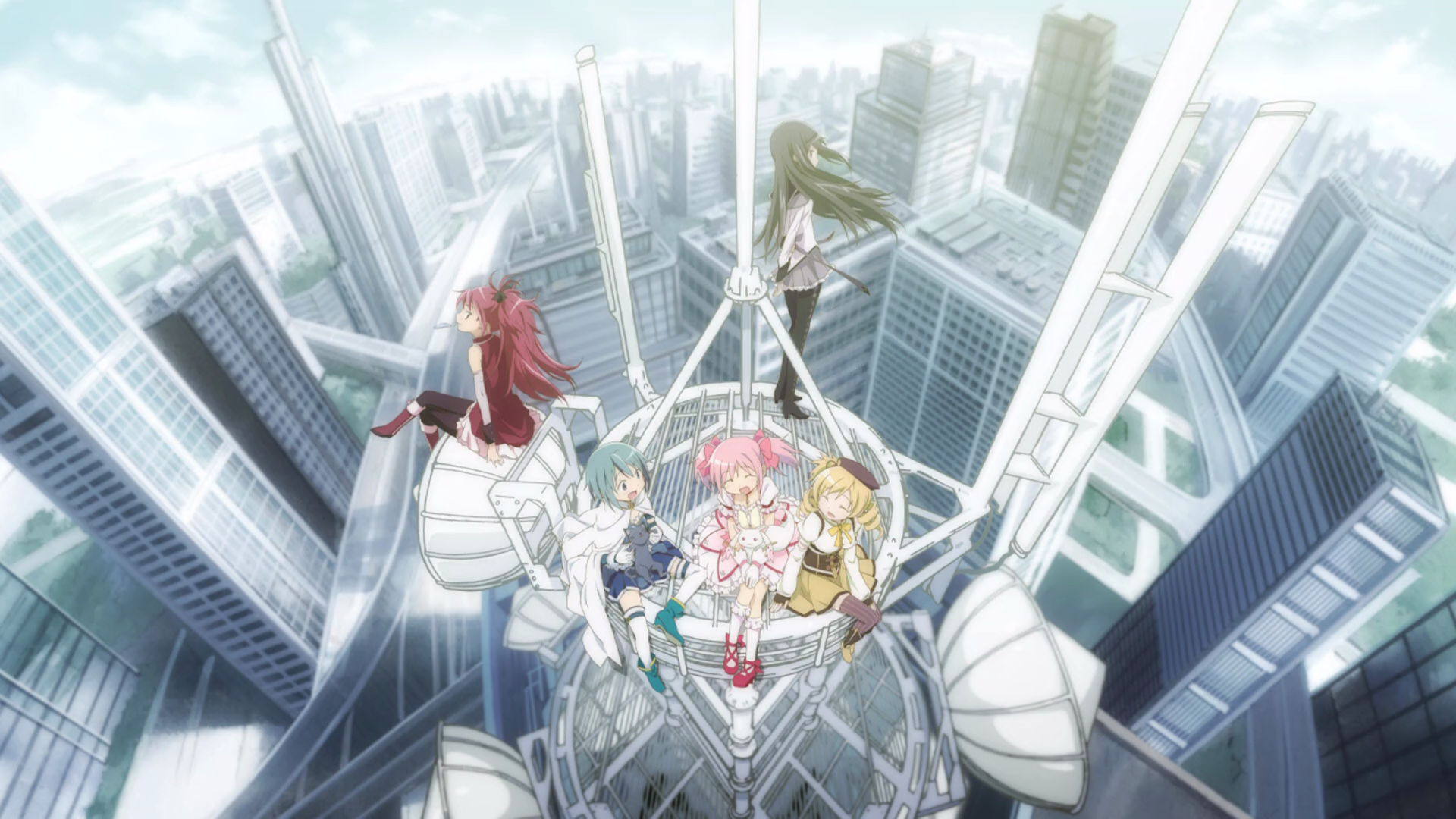

While I am loath to do any major spoiling in my overview here, I think it is a testament to the show that for all its turnarounds and revelations, it holds up to repeat viewings and—dare I say—is possibly better for it. Motivations that seemed arcane before are clear, and countless details unnoticeable the first time around are scattered throughout the narrative. And for all its slow pacing for the early part of the show, Madoka sets up what will be its biggest strength: The show really isn’t about Madoka at all. When you discover the heart of the matter, every frame becomes a cherished part of the whole.

While I am loath to do any major spoiling in my overview here, I think it is a testament to the show that for all its turnarounds and revelations, it holds up to repeat viewings and—dare I say—is possibly better for it. Motivations that seemed arcane before are clear, and countless details unnoticeable the first time around are scattered throughout the narrative. And for all its slow pacing for the early part of the show, Madoka sets up what will be its biggest strength: The show really isn’t about Madoka at all. When you discover the heart of the matter, every frame becomes a cherished part of the whole.

Because a magical girl’s soul lies within her gem, and the human body has become merely a shell for action, should the distance between the body and the gem grow too far, the ability to control the body is lost and it becomes effectively dead. As long as they are reunited, the magical girl can continue on as before, but if they are not…

Because a magical girl’s soul lies within her gem, and the human body has become merely a shell for action, should the distance between the body and the gem grow too far, the ability to control the body is lost and it becomes effectively dead. As long as they are reunited, the magical girl can continue on as before, but if they are not…

It’s an intriguing premise on its own, but when the death of someone close to Satoru results in him being framed for the crime, Revival kicks into overdrive and send him all the way back to 1988—to his childhood days where he and his classmates experience the abduction and death of fellow students. As an adult-minded Satoru relives his youth, he realizes that these murders may be the source of his misfortune in the present, perhaps the origin of everything, and he sets out to change the future.

It’s an intriguing premise on its own, but when the death of someone close to Satoru results in him being framed for the crime, Revival kicks into overdrive and send him all the way back to 1988—to his childhood days where he and his classmates experience the abduction and death of fellow students. As an adult-minded Satoru relives his youth, he realizes that these murders may be the source of his misfortune in the present, perhaps the origin of everything, and he sets out to change the future. This especially true since Satoru’s success in changing the future has as much to do with changing his relationships in the past as it does his detective work. His efforts to keep Kayo, the serial killer’s first victim, from being vulnerable and alone develop into much more, as they each discover the truth in each other and the insecurities he didn’t fully understand as a child. It’s not just Kayo, either, as Satoru reaches out and makes deeper, more profound connections with his core circle of friends, eventually enlisting them on his quest to thwart the dismal future.

This especially true since Satoru’s success in changing the future has as much to do with changing his relationships in the past as it does his detective work. His efforts to keep Kayo, the serial killer’s first victim, from being vulnerable and alone develop into much more, as they each discover the truth in each other and the insecurities he didn’t fully understand as a child. It’s not just Kayo, either, as Satoru reaches out and makes deeper, more profound connections with his core circle of friends, eventually enlisting them on his quest to thwart the dismal future. The show deftly juggles the murder mystery and everyday life, Satoru’s past and present, and spans of calm and drama in a way that neither ever outlives its welcome. It’s a mixture that thrives on each other, and the show’s pacing perfectly sets up the conclusion in a way that imminently satisfying. That’s not to say the show is without faults. One of the main antagonist’s characterization is embarrassingly thin; even the serial killer that serves as the catalyst for the entire story isn’t much better. But that’s okay, because the story isn’t really about them. It isn’t really even about the murder mystery. It’s about people treating each other with kindness, learning to see past the failings of ourselves and others, past the barriers we erect around us. And connect.

The show deftly juggles the murder mystery and everyday life, Satoru’s past and present, and spans of calm and drama in a way that neither ever outlives its welcome. It’s a mixture that thrives on each other, and the show’s pacing perfectly sets up the conclusion in a way that imminently satisfying. That’s not to say the show is without faults. One of the main antagonist’s characterization is embarrassingly thin; even the serial killer that serves as the catalyst for the entire story isn’t much better. But that’s okay, because the story isn’t really about them. It isn’t really even about the murder mystery. It’s about people treating each other with kindness, learning to see past the failings of ourselves and others, past the barriers we erect around us. And connect.

Revival—Time does not flow smoothly for you. When great misfortune, harm, or other danger happens around you, your life’s clock rewinds a few precious seconds, giving you a second chance to notice what has gone wrong. This awareness is not automatic, as you only know that you have jumped back into the past, not the exact reason for it. The greater your level in Revival, the more time your character rewinds backward, giving you longer to assess the situation and act upon it. Add your Revival Dice to any actions you manage to take during the span of time that you repeat. If you can’t discover the reason for the Revival (with Abilities like Perceptive or Sixth Sense) or act on them in time, the Revival and its Bonus dice end.

Revival—Time does not flow smoothly for you. When great misfortune, harm, or other danger happens around you, your life’s clock rewinds a few precious seconds, giving you a second chance to notice what has gone wrong. This awareness is not automatic, as you only know that you have jumped back into the past, not the exact reason for it. The greater your level in Revival, the more time your character rewinds backward, giving you longer to assess the situation and act upon it. Add your Revival Dice to any actions you manage to take during the span of time that you repeat. If you can’t discover the reason for the Revival (with Abilities like Perceptive or Sixth Sense) or act on them in time, the Revival and its Bonus dice end.