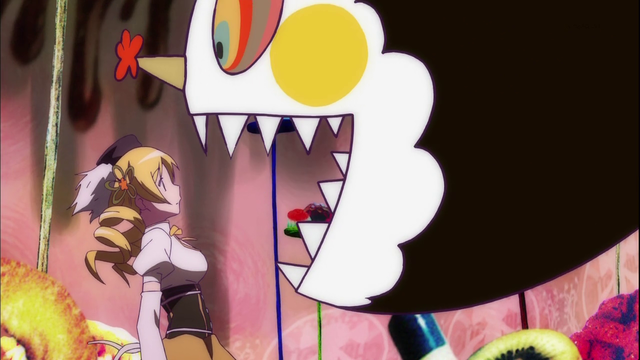

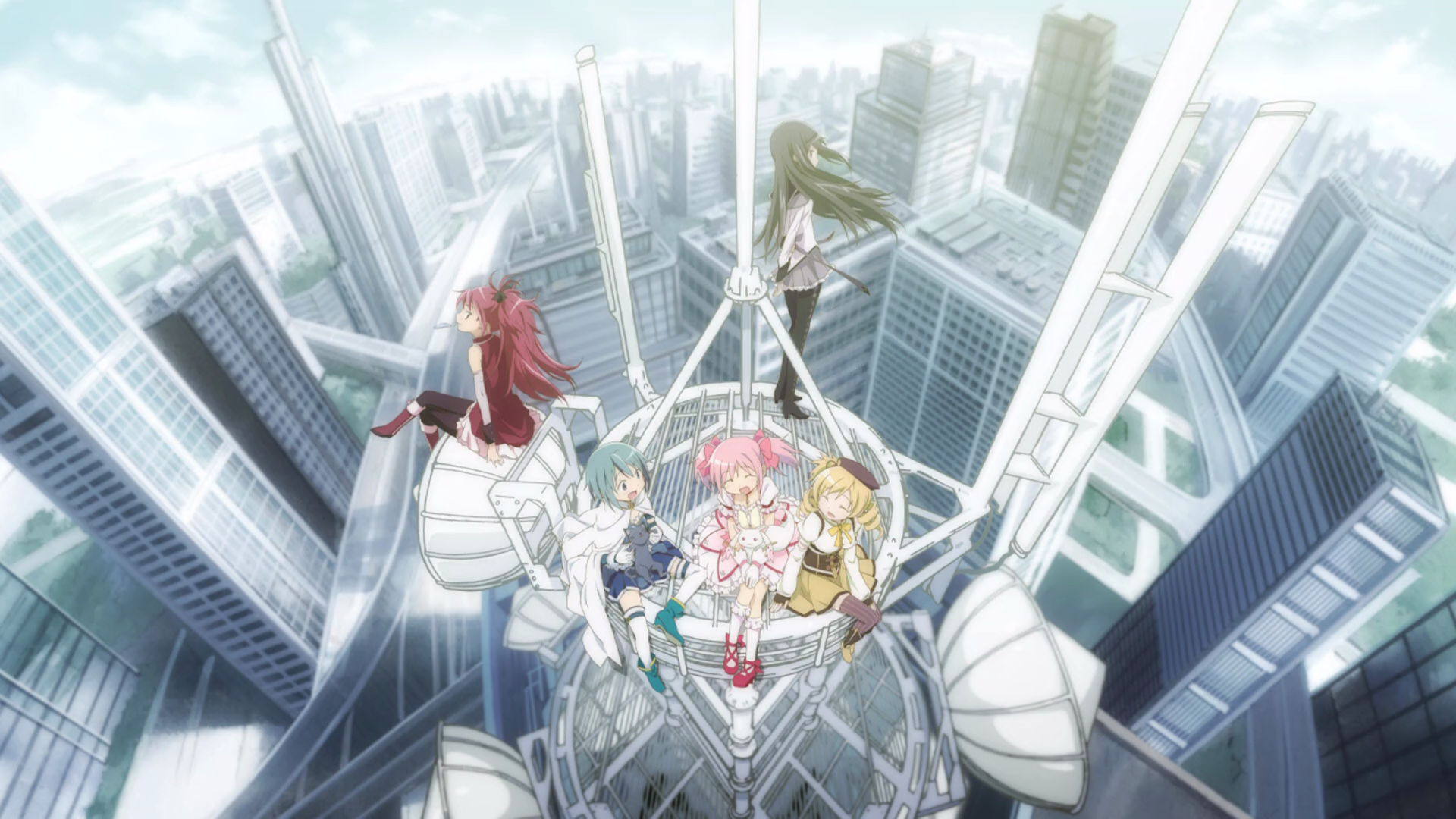

More than many series, Puella Magi Madoka Magica thrives on its world-shattering reveals, twists, and surprises, all of which come heavy and often. If you haven’t watched, but you’re thinking about it and somehow have avoided spoilers of its numerous plot doozies, here’s what you need to know: Madoka is an attempt to capture the darker realities of what being a magical girl entails—the risks, pressures, and responsibilities of having that power at such an inexperienced, impressionable age. That, and it is a show with so many helpings of moé—that amorphous Japanese ideal of cute—that anyone without at least a marginal taste for it will likely choke to death.

Though it’s not a journey without faults, among them a terribly slow start and some thin characterization here and there, Madoka succeeds where it counts, providing a deeply touching, often grim story many have wanted from the genre for a long time. And even if its deconstruction of magical girl tropes doesn’t tug at your heart strings as much as it did mine, the ethereal visuals backed by Yuki Kajiura’s extraordinary, choral-infused soundtrack are worth experiencing by themselves.

While I am loath to do any major spoiling in my overview here, I think it is a testament to the show that for all its turnarounds and revelations, it holds up to repeat viewings and—dare I say—is possibly better for it. Motivations that seemed arcane before are clear, and countless details unnoticeable the first time around are scattered throughout the narrative. And for all its slow pacing for the early part of the show, Madoka sets up what will be its biggest strength: The show really isn’t about Madoka at all. When you discover the heart of the matter, every frame becomes a cherished part of the whole.

While I am loath to do any major spoiling in my overview here, I think it is a testament to the show that for all its turnarounds and revelations, it holds up to repeat viewings and—dare I say—is possibly better for it. Motivations that seemed arcane before are clear, and countless details unnoticeable the first time around are scattered throughout the narrative. And for all its slow pacing for the early part of the show, Madoka sets up what will be its biggest strength: The show really isn’t about Madoka at all. When you discover the heart of the matter, every frame becomes a cherished part of the whole.

Put short, watch it. Even if its themes don’t resonate with you, I would be hard-pressed to believe that something, somewhere doesn’t grab you and refuse to let go.

Madoka Magica and OVA

To discuss representing the concepts of Madoka Magica in OVA without giving much of its plot away is impossible, so read onward at your own risk. Here there be spoiling dragons.

Making the Contract

To become a magical girl, a young girl must make a contract with Kyubey. In exchange for committing their lives in the service of fighting witches, they are granted a single wish. The nature of this wish has a direct effect on the powers of a magical girl. As we see in the show, wishing for the healing of her friend grants Sayaka the power of quick-healing. Homura wanting to go back in time has given her mastery over time itself, and so on. You should consider the wish and its potential carefully when making your character.

Besides the powers that are a consequence of the wish, magical girls tend to all have a basic set of Abilities, though at differing degrees depending on their potential:

- Attack (Weapon of Choice)

- Dimensional Pocket

- Magic, Arcane

Magical Girls also possess telepathy, allowing them to communicate freely with each other, Kyubey, and even normal humans without actually speaking. This is not the same as Psychic, since they cannot actually read thoughts that aren’t deliberated exchanged, nor is there any possibility to influence the thoughts of others.

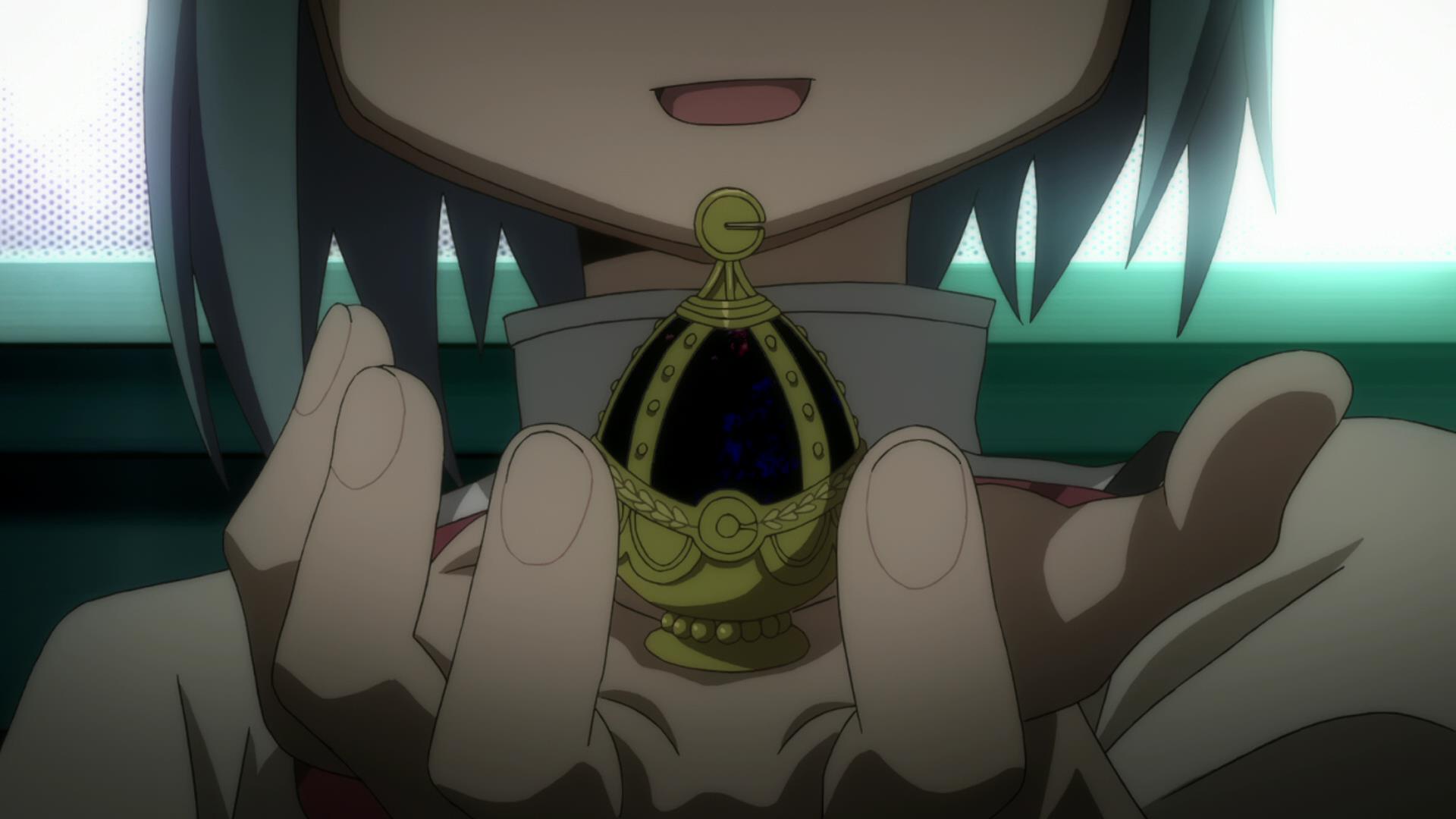

The Soul Gem

After becoming a magical girl, a character’s soul is removed from her body and encapsulated in a glowing egg called the soul gem. This is to protect the soul against the rigors of battle and to divide the character’s consciousness from the body in order to withstand the great pain fighting witches and their ilk can bring—something a conventionally mortal soul could not endure. Because of its small size and magical properties, the soul gem is relatively safe from harm, and while it remains intact, the magical girl cannot die.

However, Soul Gems can be broken. Should a character receive an attack of Damage equal to their maximum Health total, the gem is shattered and the character dies. It is also possible to target a magical girl’s soul gem directly, but few are aware of its secret (including witches) to take advantage of this.

Because a magical girl’s soul lies within her gem, and the human body has become merely a shell for action, should the distance between the body and the gem grow too far, the ability to control the body is lost and it becomes effectively dead. As long as they are reunited, the magical girl can continue on as before, but if they are not…

Because a magical girl’s soul lies within her gem, and the human body has become merely a shell for action, should the distance between the body and the gem grow too far, the ability to control the body is lost and it becomes effectively dead. As long as they are reunited, the magical girl can continue on as before, but if they are not…

Despair

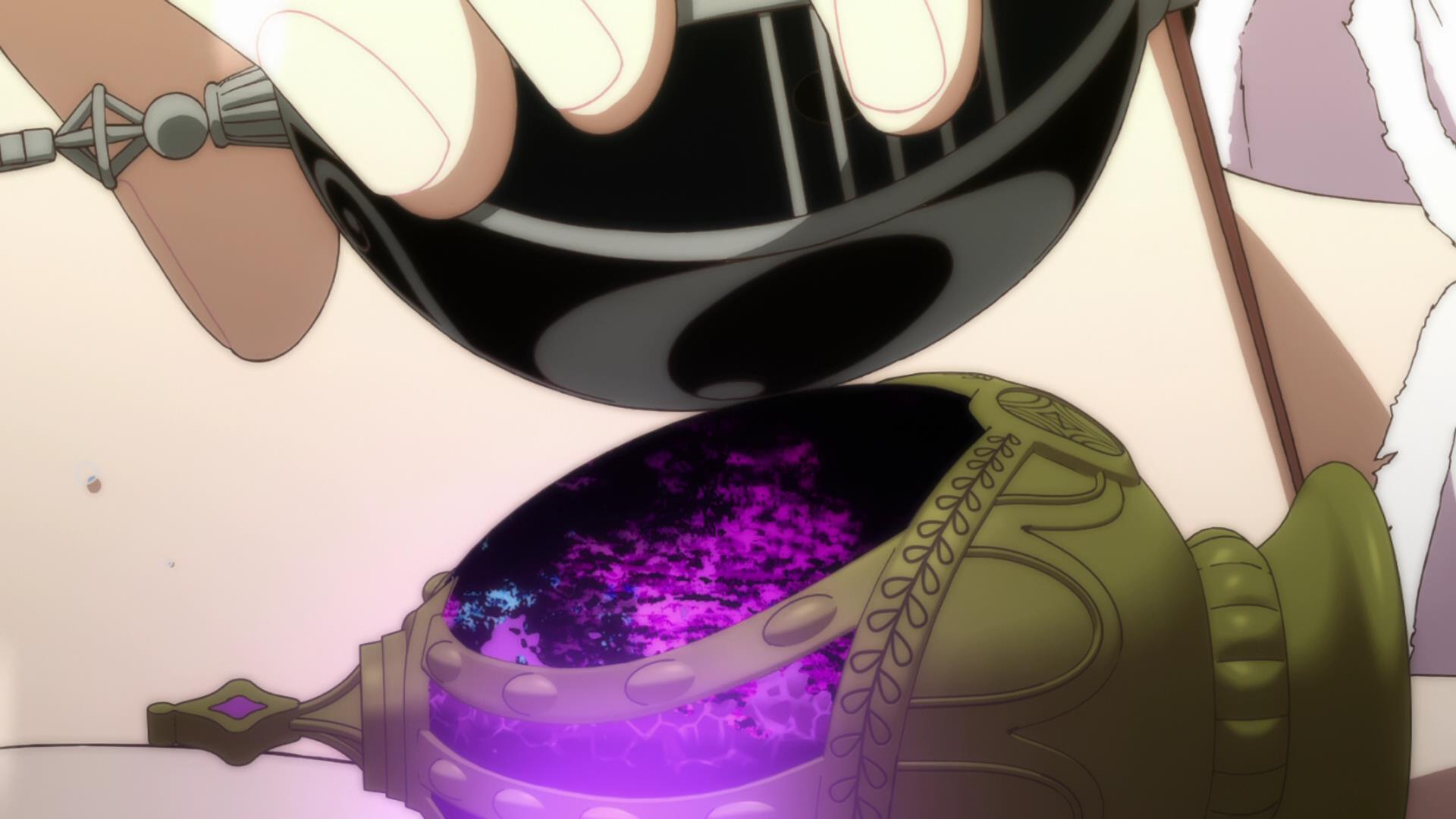

In addition to Health and Endurance, every Magical Girl has a special third total called Despair. However, instead of starting at a number and being reduced, Despair begins at zero and counts up. As the title suggests, Despair represents a magical girl’s inevitable decline to becoming a witch, but it is also the source of one of a magical girl’s greatest strengths: the ability to go beyond the limitations of Health and Endurance. At any time, characters may choose to add to Despair instead of reducing Health or Endurance. This effectively makes it possible to avoid the penalty from zeroing out one total or the other, and it also allows a magical girl to keep on fighting well beyond what would be possible otherwise. It is even possible for a magical girl to persevere without remaining Health and Endurance at all, as long as they are willing to increase their Despair. If both Health and Endurance are reduced to zero, apply a –2 penalty to all actions.

As Despair increases, the taint of a magical girl’s soul gem becomes more pronounced until it becomes entirely black, at which point it shatters and becomes a grief seed—the core of any witch. Once Despair has reached 40, magical girls must make a roll against succumbing to the overwhelming grief every time they choose to add to the Despair total. The difficulty number is equal to the tens digit of Despair. So a magical girl who has reached a Despair of 65 would roll against a difficulty of 6. 120 would be a DN of 12. And so on. Players may add Iron-Willed and other appropriate Abilities when making this roll. Likewise, Weak-Willed will prove a detriment. Once this roll is failed, the magical girl is doomed to become a witch. While exchanging dialog with other player characters or performing a few more minor actions is possible, when the plot permits, the character is lost to the world and turns to darkness.

Despair and Grief In addition to willingly increasing it, a character’s Despair may increase due to circumstances.

- 5 Distressing (A close battle, a heated argument.)

- 10 Depressing (Breaking up with a friend, realizing a core truth of being a magical girl.)

- 20 Devastating (The death of a friend or loved one.)

Despair and Time Even if a character should avoid making use of despair, the simple state of being a magical girl will taint the soul gem with time. At the beginning of every adventure after the first (presumably the one where the character made their contract) add 5 to the Despair total.

Reducing Despair There is only one way to shed Despair and return light to one’s soul gem, and that is by defeating witches and making use of their Grief Seed. The efficacy of this seed depends on the strength of the Witch—which in turn depends on the amount of Despair that the Witch had before it was transformed from magical girl. Using a grief seed removes an amount of Despair equal to half the total of the fallen magical girl it derives from.

Of course, these rules derive from the world as presented in the majority of the TV series. If you wish to set a game in the aftermath of the final episode, or even during the movie Rebellion, you will need to make some adjustments.

It’s an intriguing premise on its own, but when the death of someone close to Satoru results in him being framed for the crime, Revival kicks into overdrive and send him all the way back to 1988—to his childhood days where he and his classmates experience the abduction and death of fellow students. As an adult-minded Satoru relives his youth, he realizes that these murders may be the source of his misfortune in the present, perhaps the origin of everything, and he sets out to change the future.

It’s an intriguing premise on its own, but when the death of someone close to Satoru results in him being framed for the crime, Revival kicks into overdrive and send him all the way back to 1988—to his childhood days where he and his classmates experience the abduction and death of fellow students. As an adult-minded Satoru relives his youth, he realizes that these murders may be the source of his misfortune in the present, perhaps the origin of everything, and he sets out to change the future. This especially true since Satoru’s success in changing the future has as much to do with changing his relationships in the past as it does his detective work. His efforts to keep Kayo, the serial killer’s first victim, from being vulnerable and alone develop into much more, as they each discover the truth in each other and the insecurities he didn’t fully understand as a child. It’s not just Kayo, either, as Satoru reaches out and makes deeper, more profound connections with his core circle of friends, eventually enlisting them on his quest to thwart the dismal future.

This especially true since Satoru’s success in changing the future has as much to do with changing his relationships in the past as it does his detective work. His efforts to keep Kayo, the serial killer’s first victim, from being vulnerable and alone develop into much more, as they each discover the truth in each other and the insecurities he didn’t fully understand as a child. It’s not just Kayo, either, as Satoru reaches out and makes deeper, more profound connections with his core circle of friends, eventually enlisting them on his quest to thwart the dismal future. The show deftly juggles the murder mystery and everyday life, Satoru’s past and present, and spans of calm and drama in a way that neither ever outlives its welcome. It’s a mixture that thrives on each other, and the show’s pacing perfectly sets up the conclusion in a way that imminently satisfying. That’s not to say the show is without faults. One of the main antagonist’s characterization is embarrassingly thin; even the serial killer that serves as the catalyst for the entire story isn’t much better. But that’s okay, because the story isn’t really about them. It isn’t really even about the murder mystery. It’s about people treating each other with kindness, learning to see past the failings of ourselves and others, past the barriers we erect around us. And connect.

The show deftly juggles the murder mystery and everyday life, Satoru’s past and present, and spans of calm and drama in a way that neither ever outlives its welcome. It’s a mixture that thrives on each other, and the show’s pacing perfectly sets up the conclusion in a way that imminently satisfying. That’s not to say the show is without faults. One of the main antagonist’s characterization is embarrassingly thin; even the serial killer that serves as the catalyst for the entire story isn’t much better. But that’s okay, because the story isn’t really about them. It isn’t really even about the murder mystery. It’s about people treating each other with kindness, learning to see past the failings of ourselves and others, past the barriers we erect around us. And connect.

Revival—Time does not flow smoothly for you. When great misfortune, harm, or other danger happens around you, your life’s clock rewinds a few precious seconds, giving you a second chance to notice what has gone wrong. This awareness is not automatic, as you only know that you have jumped back into the past, not the exact reason for it. The greater your level in Revival, the more time your character rewinds backward, giving you longer to assess the situation and act upon it. Add your Revival Dice to any actions you manage to take during the span of time that you repeat. If you can’t discover the reason for the Revival (with Abilities like Perceptive or Sixth Sense) or act on them in time, the Revival and its Bonus dice end.

Revival—Time does not flow smoothly for you. When great misfortune, harm, or other danger happens around you, your life’s clock rewinds a few precious seconds, giving you a second chance to notice what has gone wrong. This awareness is not automatic, as you only know that you have jumped back into the past, not the exact reason for it. The greater your level in Revival, the more time your character rewinds backward, giving you longer to assess the situation and act upon it. Add your Revival Dice to any actions you manage to take during the span of time that you repeat. If you can’t discover the reason for the Revival (with Abilities like Perceptive or Sixth Sense) or act on them in time, the Revival and its Bonus dice end.

But Spike isn’t just sort of good at both, he’s great. And if you couldn’t create Spike with ease in OVA, then that’s as much of a litmus test as anything. With that in mind, I condensed every combat skill into an Ability called, well, Combat Skill. With one attribute, your character was adept at attacking, whatever form that takes. Sure, it flies in the face of most RPG design that routinely compartmentalize such things, but it just made things so much easier. You could still just do one thing, of course, but if you ever wanted to branch out, you weren’t punished for it.

But Spike isn’t just sort of good at both, he’s great. And if you couldn’t create Spike with ease in OVA, then that’s as much of a litmus test as anything. With that in mind, I condensed every combat skill into an Ability called, well, Combat Skill. With one attribute, your character was adept at attacking, whatever form that takes. Sure, it flies in the face of most RPG design that routinely compartmentalize such things, but it just made things so much easier. You could still just do one thing, of course, but if you ever wanted to branch out, you weren’t punished for it. While this was easily the most gratifying change to OVA, there’s a vast variety of additions and improvements that I’m also fond of. The original game’s “knockback” was split into three separate combat complications, giving more tactical options to the otherwise streamlined rules. Looking at these, I realized that I could take the same concept and apply them outside of combat, and Succeeding with Complications was born. While I won’t be foolhardy enough to claim this is an entirely new idea (Fate, if nothing else, pushes the “fail forward” concept hard), I’m really please with how neatly it fits into OVA and brings combat and out-of-combat closer together thematically.

While this was easily the most gratifying change to OVA, there’s a vast variety of additions and improvements that I’m also fond of. The original game’s “knockback” was split into three separate combat complications, giving more tactical options to the otherwise streamlined rules. Looking at these, I realized that I could take the same concept and apply them outside of combat, and Succeeding with Complications was born. While I won’t be foolhardy enough to claim this is an entirely new idea (Fate, if nothing else, pushes the “fail forward” concept hard), I’m really please with how neatly it fits into OVA and brings combat and out-of-combat closer together thematically.

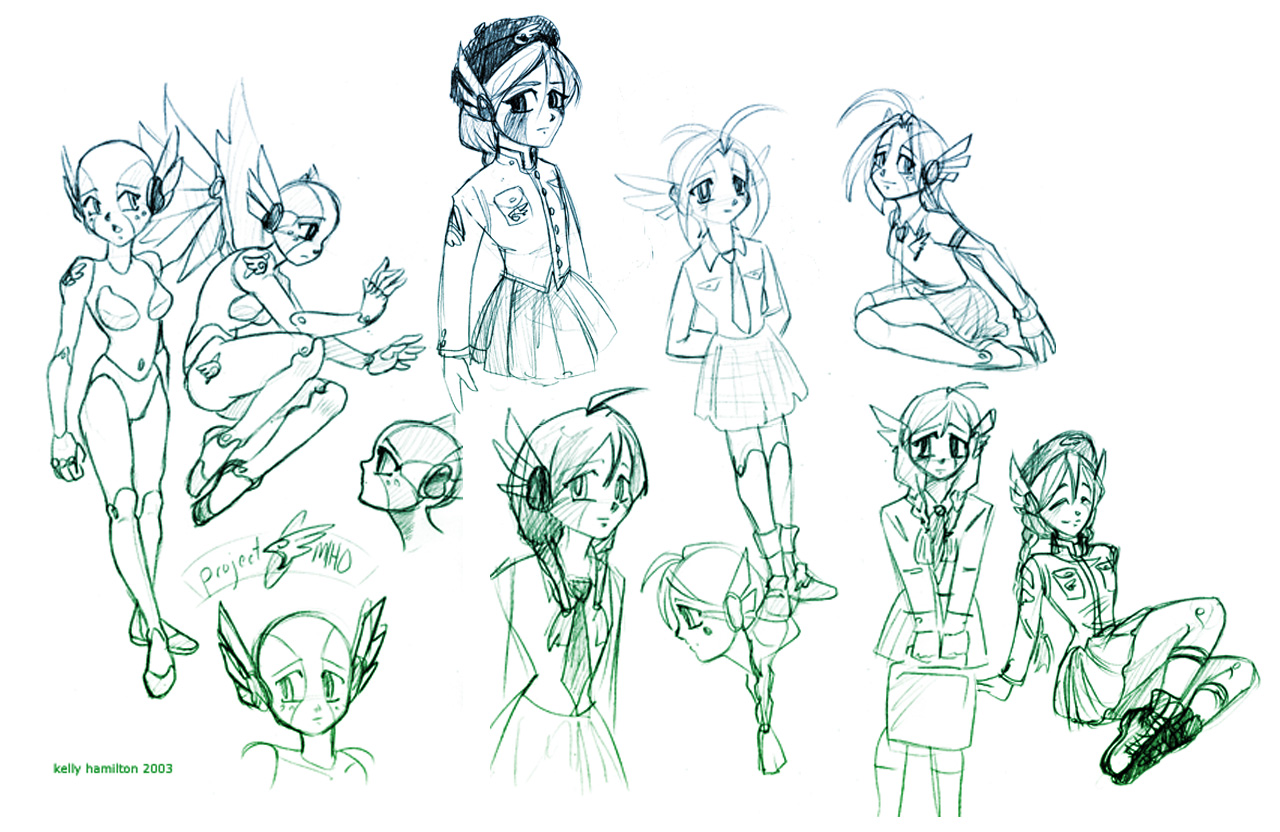

The military-inspired uniform makes its first appearance here and was used for her final design. This iconic ensemble would go on to be featured (more or less) in the revised game, despite the fact that most other character designs changed completely.

The military-inspired uniform makes its first appearance here and was used for her final design. This iconic ensemble would go on to be featured (more or less) in the revised game, despite the fact that most other character designs changed completely. Oh, and if you’re wondering about my illustrations mentioned earlier, here’s a final comparison featuring everyone’s favorite copper, Jiro.

Oh, and if you’re wondering about my illustrations mentioned earlier, here’s a final comparison featuring everyone’s favorite copper, Jiro. Slight improvement, right?

Slight improvement, right?