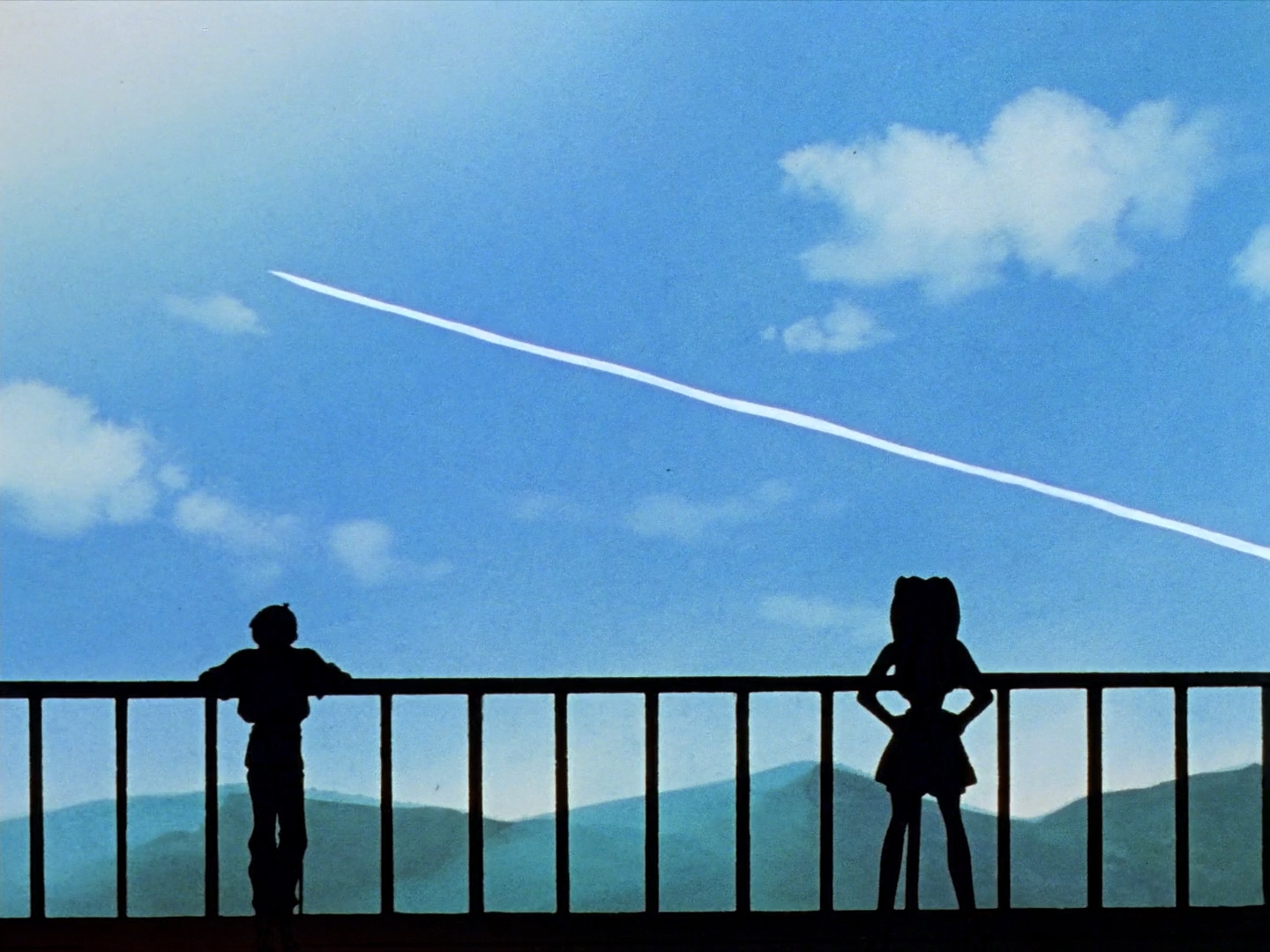

As much as any one show can, Evangelion seems to encompass what anime is. Towering mecha duking it out with even more massive monsters, cutesy animal mascots, catchy opening music, and two candidates for “best girl” that have engendered debates going on for two decades now.

But as the episodes go by, this begins to feel less and less true. Those marvels of mechanical might, the show’s “Eva,” are almost indescribably unsettling. The solid, purposeful movements of their super robot show forebears are replaced with agile, animalistic strides; metallic joints flex and tighten in supple, organic ways; and instead of serving solely as window to the pilot themselves, we see a robot that is alive with growls and groans and wounds that ooze and bleed.

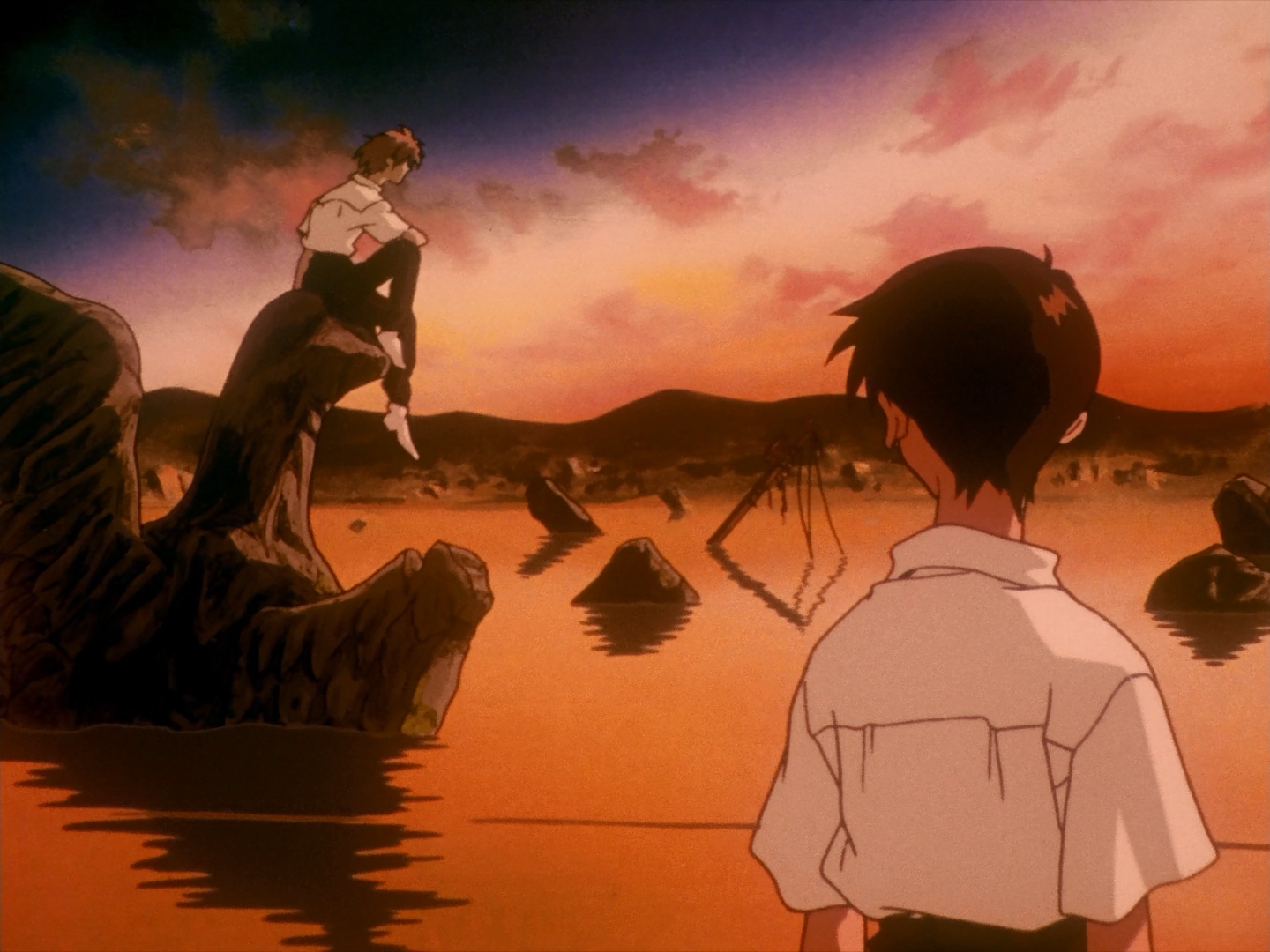

The pilots, too, defy expectation. These are not plucky, self-assured heroes ready to save the world. They’re children, children who strive for the approval and affection of the adults around them, but find only demands and expectations in return. Anime-whipping-boy Shinji is often portrayed as a whiner by fans, but if anything, through most of the show’s run he readily submits himself to a job time and again that, rightly so, terrifies him—just so he achieve what he desires most: attention from his father.

Shinji is hardly alone in this regard. Asuka blusters and postures in an attempt to appear the self-sufficient adult in the face of a mother who abandoned her. Rei, who knows no life at all but to be used, struggles to understand relationships beyond the immutable tool dynamic forced upon her. Even characters like Misato and Ritsuko, full-grown adults, struggle with the remnants of their own childhoods and parental trauma and deal with it in flawed, self-destructive ways.

The show reveals this to us, little by little, in the guise of a monster-of-the-week show. An “Angel” shows up, bringing with it its own unique conundrum that must be solved before the episode’s end. Our youthful pilots are forced to confront their doubts and shortcomings, whether it’s Shinji’s trepidation about “getting in the robot”, his synchronizing with Asuka—and thus being forced to form an emotional connection with someone—in one of the series’ highlight episodes, or dealing with the inherent morality of being arbiters of life and death. As Evangelion goes through the motions of the genre it embodies, it deconstructs it in meaningful, interesting ways.

But no matter how many Angels there are to defeat, no matter how many tribulations must be triumphed over, what every character in the show wants, really, is to be loved—to be accepted for the flawed, broken people that they are. Even the infamous Gendo Ikari, for all his glasses flashing, finger temple-ing, abysmal parenting, is only seeking to recapture the love he has lost while failing completely to impart that same love to his son.

But as the show hurtles on to its conclusion, any semblance of careful pacing is thrown out the window. Gone are the bits and pieces of character development interspersed with tense action sequences and breath-catching moments of levity. Instead we are treated to diatribes of incomprehensible technobabble that, instead of buoying our characters’ development, threaten to overshadow them at every turn. The introduction of Kaoru, a seminal encounter in Shinji’s aspiration for acceptance, rushes through its character arc in a mere 25 minutes, something that could’ve lasted an entire season, and in doing so obliterates any chance to inspire the emotional connection it strives to impart.

And then we find ourselves reaching Evangelion’s controversial climax—the ending the franchise has spent the better part of this millennium rewriting over and over. The truth of the matter is it’s not a bad ending at all. The entire show has been building up to this moment in Shinji’s life, this monologue of introspection where Shinji really has to deal with his anxiety and depression without hiding or running away.

But the moment is buried under baffling reused animation clips and the dangling questions of the shows’ own plot. What has been Seele’s goal all along? Gendo Ikari’s? What are the Dead Sea Scrolls? What were the Angels? What is this Human Instrumentality Project introduced in the show’s eleventh hour? It’s hard to cast blame for disliking an ending that feels so woefully incomplete. But if you’re willing to write away these questions as window dressing, or supplement your viewing with a bit of research, Eva’s ending encapsulates a complete catharsis of Shinji’s struggle—and as such is a much more satisfying ending that the more explicitly explained (yet somehow even more discombobulating) End of Evangelion.

But perhaps this incompleteness is as much a part of Evangelion’s enduring appeal as its memorable characters and awe-inspired designs. As the show takes its journey from sumptuously animated straight-up action romp to avant guard stream-of-consciousness introspection, there is a spot on this crazy train for everyone. And perhaps that’s why no single end-of-the-line is ever going to appease everyone. Like Shinji, perhaps Evangelion is something we simply ask too much from.

Perhaps that’s about as fitting a legacy as you’ll get.

Evangelion and OVA

Despite the length I go to demonstrate Eva’s super-robot trappings as a frame for a story about the human condition, inevitably the first question most people will ask about representing Eva in OVA is “How do we make the mecha go boom-boom?”

The answer is pretty straightforward. None of the Evas demonstrate any specific strengths or weaknesses, and even their armaments tend to be slave to the plot as opposed to anything concretely measured or differentiated. Just stat up capable combatants with decent points in “Attack” and you’ll be hard-pressed to go wrong.

What Evangelion does bring to the table that’s inherently interesting is the Eva units almost complete lack of a self-sustaining power-source. Without being literally plugged in, Evas run out of juice within minutes. It’s a fascinating wrinkle to the Angel-fighting hijinks, and one that immediately sets Evangelion apart from other giant robot-style shows.

Racing Against the Clock

Time is relatively abstract in OVA. You won’t find passages in the text extolling that a round is ten seconds long, or that a given action chips off a discrete amount of time from a hypothetical clock. For most narrative purposes, this works just fine.

But sometimes time matters—really matters. Evangelion drives this concept home when the Evas become separated from a dedicated power source. Whether due to severed plugs, long-distance deployment, or enemy interference, as much as the Angels themselves, time is the enemy.

That’s not to say one should adopt the ten-second round or anything so pedantically concrete. Despite the explicitly defined “five minutes” of the show, the narrative beats stretch and contract to fit whatever the plot demands. It is a constraint, but an elastic one.

So instead of setting a real-world time frame, it’s more prudent to simply assign a number of “Beats.” 10 is a decent amount, but this can be expanded or reduced as the Game Master sees fit. Likewise, the Game Master can increment the clock at any time. You could do this once a round, but also consider the narrative flow of the story:

- A character completes an action that takes a step towards a goal—or prevents another from completing their own.

- A character has dealt or received a significant chunk of damage. (Ie. by inflicting/incurring the zero Health Penalty.)

- An NPC provides useful information that contributes to the current conflict.

Also certain rolls will affect the spending of Beats.

- If a character has an Amazing Success, or inflicts a complication, that action will never spend a Beat.

- If a character fails an action of importance, it will always spend a Beat. (Missing in Combat does not count.)

But the flow of time is not solely at the Game Master’s discretion or the whim of the dice. The Players can use time to their advantage, or expend more of themselves to get the job done a little faster.

- A character may spend Drama Dice (or incur a –1 Penalty) to buy off a Beat that would ordinarily be spent.

- A character may get a Drama die by spending an extra Beat.

Obviously when there are no more Beats, time has run out! Hopefully the PCs have plenty of Endurance to burn to keep that from happening!

…By the by, that whole “best girl” thing I mentioned earlier? There’s only one right answer.